Kweetngom Kuba royal drum

- Inventory number: MO.1995.16.1

- Made (in the 1920s?) at the request of Nyimi (king) Kot Mabiintsh ma-Kyeen (reign: 1919-1939)

- Sold to the museum by Nyimi Kwete Mbokashanga in June 1995 for 200,000 Belgian Francs (approximately 5,000 euros).

A recent acquisition

This Kuba royal drum entered the collections of the Tervuren museum in 1995. It was bought directly from the Kuba Nyimi along with 8 other pieces (3 masks, 1 cup, 2 boxes, 1 sceptre and 1 fly whisk) that the king had brought to Belgium during a stay in Europe.

Among the 9 objects purchased from the Nyimi is also a fly whisk (inventory no. EO.1995.12.2), for which no photograph is yet available.

The Nyimi had been in contact for many years with the museum's curators, particularly the ethnomusicology section curator, to whom he had proposed selling this drum on several occasions. The drum was eventually acquired in June 1995 for the sum of 200,000 Belgian Francs.

At the time, the purchase was justified by the institution's collection managers based on two criteria (note 09/06/1995):

- enhancing the collections, because there was no other object like it in the museum

- the piece's significant cultural value (artistic and especially historical).

Importance of the pelambish

Indeed, according to the first director of the Institut des Musées nationaux du Congo, the pelambish drum, such as this one, is "the royal drum par excellence" (J. Cornet 1982: 296). Rarely beaten, "except at the start of royal dances and on the day of the new moon", it is primarily a symbol of the royal presence and, as such, stands next to the wisdom basket during important ceremonies. As a rule, each king must have a drum made for his reign. The drum then bears the name of its distinguished commissioner (certain kings have had several made). These drums are normally kept at the palace.

Of the five pelambish drums recorded by Cornet in the 20th century, four were purchased at the beginning of the 1970s by the Institut des Musées nationaux du Zaïre and are kept in the Congo national museum collections in Kinshasa: inv. 70.8.1; 70.8.2; 73.381.1 and 73.381.2 (see photos below).

The last two of these examples were commissioned by Nyimi Mbopey Mabiintsh ma-Kyeen, who reigned from 1939 to 1969. These two drums are replicas, created by the same artist, of a fifth and older drum commissioned by Nyimi Kot Mabiintsh ma-Kyeen (reign: 1919-1939), which was kept at the palace in the capital Nsheng until the 1990s (at the centre of the photo below). It is this drum that was bought by the Tervuren museum in 1995.

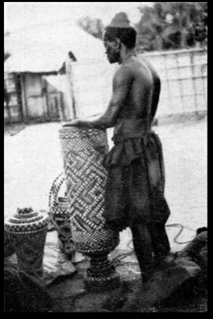

Court art - Traditional art - Living art

This drum is well known as regalia of the Kuba Kingdom. It was photographed in the 1940s in the capital Nsheng, an image published by Gaston-Denys Périer in the work Les arts populaires du Congo belge in 1948. This prolific author and leading promoter of the Congo arts in Belgium during the first half of the 20th century, staunchly supported the conservation of Congo heritage objects with a view to maintaining the country's "living tradition". His choice of image, showing the contemporary in-situ use of Kuba regalia, was certainly not by chance.

Kuba arts were highly popular with Westerners from the early 19th century, which led to an early and massive dispersal of these works to Europe. This problem did not stop with the end of colonisation, but continued during the post-colonial period, significantly pushing up the financial value of these pieces on Western markets.

Legislation and export

At the instigation of figures like Périer, the Belgian Ministry of Colonies attempted, in the late 1930s (Decree of 16 August 1939), to control and limit the export of objects of Congolese cultural heritage. Heritage listing measures were introduced, but remained essentially restricted to monuments and sites. After independence, the issue of heritage protection became the responsibility of the Congolese government. In March 1971, it enacted a law (no. 71-016) designed to make an export certificate obligatory for antique objects. The managers of the Tervuren museum were aware of this measure as it had been initiated by Lucien Cahen, the director of the Belgian museum and of the national institute in Kinshasa at that time.

Initially complicated to implement (Tshiluila, 2007), the law became even more difficult to enforce during the profound political crisis of the Mobutu presidency in the 1990s.

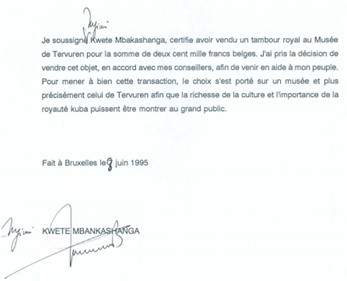

Although there is no export certificate associated with the drum's acquisition, the Nyimi nevertheless signed a document on the occasion, dated 8 June 1995, in which he stated:

"Je soussigné, Nyimi Kwete Mbakashanga, certifie avoir vendu un tambour royal au Musée de Tervuren pour la somme de deux cent mille francs belges. J’ai pris la décision de vendre cet objet, en accord avec mes conseillers, afin de venir en aide à mon peuple. Pour mener à bien cette transaction, le choix s’est porté sur un musée et plus précisément celui de Tervuren afin que la richesse de la culture et l’importance de la royauté kuba puissent être montrer (sic) au grand public."

"I the undersigned, Nyimi Kwete Mbakashanga, declare that I have sold a royal drum to the Tervuren Museum for 200,000 Belgian Francs. I have decided to sell this object, in agreement with my advisers, to assist my people. It was decided to carry out the transaction with a museum, and more precisely the Tervuren museum, to ensure that the cultural wealth and importance of the Kuba kingdom can be shown to the wider public."

The purpose of this declaration seems to have been to circumvent the legal implications of such a purchase; but the legitimacy of the Nyimi to export an item to Belgium without a certificate remains questionable according to the stipulations of the Congolese government.

The sole responsibility of the Nyimi in the decision to sell an object of cultural significance was in fact a source of recurring tensions between the Kuba kingdom and the Congolese national authorities.

Between the 1970s and the early 2000s, the Nyimi Kwete Mbokashanga often sold Kuba objects on the art market in Congo and in the West.

This commercial exploitation of Kuba tangible cultural heritage is in line with its prestige value, which helped to promote the Kuba kingdom through grand events and exhibitions as well as through "diplomatic gifts" (gifts and gifts in return), throughout the colonial and post-colonial periods. In such political circumstances, which were marked by numerous periods of crisis, Kuba art helped to maintain the kingdom, whose position was also sustained in part by Kuba art and the income it generated (Vansina 2007).

Another acquisition from the Nyimi

None of the other objects bought from the Nyimi in 1995 are currently exhibited in the museum.

However, in the middle of the Rituals and Ceremonies Room is an impressive Kuba royal mask, the costume for which was also sold by Nyimi Kwete Mbokashanga in 1980 to the Société des Amis, the society of friends of the museum. The latter donated it to the museum, along with a metal bell and a woman's wrap skirt, which are not on display.

The belt presented with this costume is also an older donation from the Société des Amis and was also obtained from the Kuba Nyimi, Kwete Mbokashanga's predecessor.

In her recent work, historian Sarah Van Beurden (2015: 199) reveals that the sale of Kuba art objects continued throughout the period 1970-1980 to such an extent that certain dances could no longer be performed because their costumes, particularly the women's ceremonial wrap skirts, had been sold both abroad and to the Institut des Musées nationaux du Zaire.

While the growing disappearance of objects led to tension against the Nyimi within the kingdom (the Kuba women threatened to relieve the king of his functions), the production of Kuba art also adapted to the high demand for objects with the development of a crafts trade and the production of objects specifically for export.

Text compiled from a draft by Agnès Lacaille based on specific research and a synthesis of the data below.

SOURCES

Interviews, correspondence, unpublished sources:

- Anne-Marie Bouttiaux

- Rémy Jadinon

- Sarah van Beurden

- Hein Vanhee

Archives

Ethnographic section, acquisition records: "Amis du Musée", "Kwete Mbokashanga"

Works

- Cornet J., Art royal Kuba, Milan, Sipiel, 1982, pp. 296-299

- Périer G.-D., Les arts populaires du Congo belge, Collections nationales, 8e série n° 90, Bruxelles, Office de Publicité, 1948.

- Tshiluila J. S., "Le patrimoine culturel et naturel au Congo à l’époque coloniale", in Quaghebeur & Kalengayi (dir.), Aspects de la culture à l’époque coloniale en Afrique centrale. Volume 6. Formation. Réinvention, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2007, pp. 63-89

- Van Beurden S., Authentically African. Arts and the transnational politics of Congolese Culture, Ohio University Press, 2015

- Vansina J., "La Survie du Royaume Kuba à l’époque coloniale et les arts", Annales Aequatoria, 28, 2007, pp. 5-29.

The information contained in this article is mostly based on resources available at the museum (archives, publications, etc.). The object's biography can therefore still be developed further. Do you have any comments, information or stories to share about this object or this type of object? Please contact us at: provenance@africamuseum.be.

In the framework of the Taking Care project.