RMCA publications

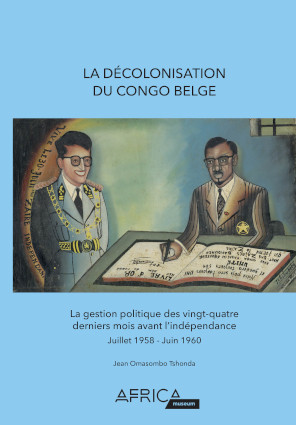

La décolonisation du Congo belge. La gestion politique des vingt-quatre derniers mois avant l'indépendance Juillet 1958 - Juin 1960

Dès juillet 1958, la situation politique du Congo belge se modifia à un rythme soutenu et cela ne s'arrêta plus. À l'initiative du ministre Léon Pétillon, une commission constituée de sept personnalités belges reçut du gouvernement belge la mission de recueillir les aspirations et les vues de la « population blanche et noire du Congo ». Aucun Congolais n'en faisait partie, une absence durement ressentie par les colonisés. Début novembre 1958, Pétillon quitta le gouvernement, malgré l'opposition du roi. Cet ancien gouverneur général promu ministre des Colonies, observait qu'aucun changement ne paraissait plus possible. Son successeur Maurice Hemelrijck, perçu au départ comme un habile diplomate, créa la polémique parce qu'il exigeait l'amélioration des relations sociales entre Blancs et Noirs. Il démissionna début septembre 1959, se sentant impuissant face à l'impasse dans laquelle la Belgique se trouvait. Au Congo, les opinions étaient devenues irréconciliables et la Belgique, acculée, octroya l'indépendance sans en avoir clairement défini les contours. Tout était à discuter, tout était à marchander, sous l'effet de la colère des uns et de l'anxiété des autres.

Entre juillet 1958 et juin 1960, tout allait donc se décider. La rapidité et la multiplicité des interventions politiques émaillèrent une décolonisation tardivement déclenchée qui traduisait le refus d'une main tendue par les coloniaux aux colonisés pour qui « les jours du colonialisme étaient révolus ». L'indépendance fut le résultat d'un chaos…

Cet ouvrage est un récit chronologique, portant sur des faits précis, étayés par une iconographie adaptée. L'auteur n'interprète pas, mais puise dans les attitudes et les témoignages des principaux acteurs de l'indépendance de la République démocratique du Congo dont est commémoré en 2020 le soixantième anniversaire.

***

Als we het hebben over de dekolonisatie van Belgisch-Congo denken we in de eerste plaats aan de toespraken van enerzijds Belgisch staatshoofd Boudewijn I en anderzijds Congolees eerste minister Patrice Lumumba tijdens de onafhankelijkheidsceremonie op 30 juni 1960 in Leopoldstad. Op die dag verdedigden beiden hun diametraal tegengestelde visie op de kolonisatie. Wat deze toespraken wél gemeenschappelijk hebben is dat ze duidelijk de argumenten van de Belgen en de Congolezen weergeven die aan de basis van de dekolonisatie liggen. Vandaag zindert de echo ervan nog na; het heden wordt immer voortdurend geconfronteerd met de geschiedenis, die het als het ware ‘besmet'.

Sinds juli 1958 is de politieke situatie in Belgisch-Congo gestaag blijven veranderen. Minister Léon Pétillon richtte een commissie op die bestond uit zeven Belgische personaliteiten, bevoegd om een lijst op te maken van de verlangens en opinies van de ‘blanke en zwarte bevolking van Congo'. Geen enkele Congolees maakte hier deel van uit; dit gemis liet zich heel erg voelen onder de gekoloniseerden. Begin november 1958 verliet Pétillon de regering, zeer tegen de zin van de koning. De oud-gouverneur-generaal, gepromoveerd tot minister van Koloniën had immers vastgesteld dat geen enkele verandering nog mogelijk was. Zijn opvolger, Maurice Hemelrijck, die aanvankelijk gezien werd als een bedreven diplomaat, zaaide polemiek door een verbetering te eisen in de sociale relaties tussen blanken en zwarten. Hij nam ontslag begin september 1959, machteloos tegenover de impasse waarin België verkeerde. In Congo bleken de meningen onverzoenbaar en België, in het nauw gedreven, kende de onafhankelijkheid toe, zonder echter duidelijk de krijtlijnen hiervoor te hebben uitgetekend. Woede langs de ene kant, angst langs de andere, leverde nog heel veel stof voor discussie en onderhandeling,

Alles zou dus beslist worden tussen juli 1958 en juni 1960. De snelheid waarmee een veelvoud van politieke interventies werden doorgevoerd verbloemde een dekolonisatie die pas laattijdig op gang kwam. Ze toonde duidelijk aan dat de kolonialen weigerden de hand te reiken aan de gekoloniseerden, voor wie ‘de dagen van het kolonialisme verstreken waren'. De onafhankelijkheid was het resultaat van chaos …

Dit werk is een chronologische beschrijving, met betrekking tot welbepaalde feiten, met bijpassende beelden ter illustratie. De auteur interpreteert niet, maar put uit de houding en de getuigenissen van de belangrijkste actoren van de onafhankelijk van de Democratische Republiek Congo, waarvan in 2020 de zestigste verjaardag van de onafhankelijkheid wordt herdacht.

***

The speeches delivered on 30 June 1960 in Leopoldville during the independence proclamation ceremony – one by the Belgian monarch Baudouin I and the other by Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba – are the dominant image of the decolonization of Belgian Congo. On that day, each of the two men defended their version of colonization, an exercise that revealed diametrically opposed views. But the relevance of the speeches lies in the arguments for decolonization that were advanced by Belgians and Congolese. The echoes of those speeches can still be heard to this day, as the present grapples with a past that taints it.

Changes in the political situation of Belgian Congo began picking up speed in July 1958 and never let up speed. At the initiative of the minister Léon Pétillon, a commission of seven Belgian dignitaries were tasked by the government to put together the aspirations and viewpoints of ‘the white and black population of Congo'. Not a single Congolese was on the commission, an absence felt sharply by the colonized. In early November 1958, Pétillon left the Belgian government against the king's wishes. The former governor-general, promoted to Minister of the Colonies, observed that change no longer seemed possible. His successor Maurice Hemelrijck, initially seen as a skilled diplomat, sparked controversy because he demanded an improvement in the social relations between Blacks and Whites. Feeling powerless in the face of the impasse that Belgium found itself in, he resigned in early September 1959. In Congo, differences had become irreconcilable and a cornered Belgium granted independence without clearly defining the form it would take. Everything was up for discussion and bargaining, under the anger of some and the anxieties of others.

It all had to be decided upon between July 1958 and June 1960. The rapidity and proliferation of political interventions punctuated a delayed decolonization that mirrored the rejection of a hand extended by the colonizers to the colonized, for whom ‘the days of colonialism were past'. Independence was borne of chaos.

This book provides a chronological account, based on precise events and illustrated by relevant images. Rather than interpreting, the author draws on the attitudes and testimonials of the key individuals in the independence of the Democratic Republic of Congo, which will celebrate its sixtieth anniversary in 2020.