Publications du MRAC

République démocratique du Congo. Kasaï-Oriental, un nœud gordien dans l'espace congolais; Désormais gratuitement disponible sur / Vanaf nu vrij beschikbaar op / From now free available on http://www.africamuseum.be/research/publications/rmca/online/index_html/

Au plan administratif, elle regroupe l'actuel district de Tshilenge et la ville de Mbujimayi. Moins grande que la ville de Kinshasa, son espace correspond à l'ancien territoire de Bakwanga, fonctionnel en 1960. C'est la seule des 26 provinces décentralisées à être mono-ethnique, habitée presqu'exclusivement par les Luba Lubilanji. Ses entités politico-administratives, qui n'ont pas connu le démembrement des groupements locaux constitutifs de la période coloniale, ont toutes été élevées à un rang supérieur à partir de l'indépendance, l'ancien territoire recevant le statut de district. Ces changements sont liés aux mouvements des populations (avant et, surtout, avec la décolonisation) qui fondèrent l'origine brutale de la ville de Mbujimayi.

Bien avant la colonisation, le dynamisme démographique de la région luba était déjà relevé par les esclavagistes ; de réservoir d'esclaves qu'elle était alors, elle deviendra ensuite un vivier en main-d'œuvre pour les entreprises coloniales. Conjugués à la maladie et la famine qui sévissaient, ces facteurs participeront à la dispersion du peuple luba à travers le pays, essentiellement dans les grands centres d'exploitation, le long du chemin de fer BCK et au Katanga (UMHK). Voilà situé un des fondements de leur exclusion : la dichotomie entre le monde rural et le monde urbain a privé les Luba d'une base sociale, nécessaire à l'entreprise de la conquête du pouvoir. Leur position sociale dans les centres urbains, notamment dans les ceintures urbanisées du Katanga et de Luluabourg (Kananga) avait été perçue, aussi bien par les Luba eux-mêmes, obligés de se créer des solidarités urbaines, que par les « Katangais authentiques » et les Lulua, pour qui le prisme ethnique expliquait leur marginalisation économique et professionnelle. Sans solide incitant au retour dans leur région d'origine, l'élite luba se redirigea vers une vocation nationale, non sans entraîner tout le groupe luba dans sa démarche, avec des conséquences parfois dramatiques. C'est le cas au moment de l'indépendance lorsqu'il s'était constitué en un espace autonome de gestion politique et, puis, dès le début des années 1990 en espace monétaire couplé d'une identité politique forte.

Cet ouvrage plonge au cœur du pays luba lubilanji, une terre de religions, où s'entrecroisent des groupements/clans aux rapports souvent fort complexes. La forte densité de peuplement, exacerbée par les migrations et couplée à la présence du diamant dans le sous-sol, n'est pas sans engendrer des conflits fonciers intenses.

Les Luba Lubilanji aux références socioculturelles enchevêtrées se réclament d'un même ancêtre, Nkole, et partagent une langue commune, le tshiluba. Ils se reconnaissent comme un tshisa (peuple) organisé en clans, dits « bisamba » (Bakwa ou Beena), distincts. À la fin du XIXe siècle, la carte de la mise en place de ces populations faisait état de 55 de ces groupements/clans, dont 25 situés dans la région correspondant au Kasaï-Oriental.

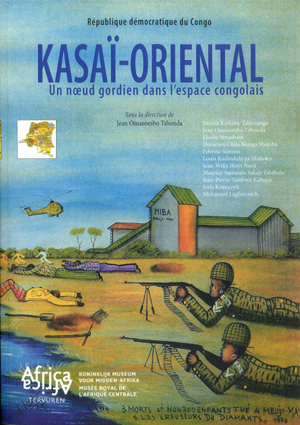

La vie socio-économique de la région luba est restée tributaire presque exclusivement de l'économie du diamant, exploité d'abord par la Forminière puis par la Minière de Bakwanga (MIBA). Depuis l'indépendance, l'extraction artisanale a progressivement pris le pas sur le mode industriel, une tendance déjà encouragée en 1960 par Albert Kalonji à travers son fameux article « 15 Bakwanga», et surtout favorisée en 1982 par la nouvelle libéralisation des ressources minières décidée par le régime Mobutu, accédant ici aux exigences des représentants politiques luba. Mais malgré les richesses que génère son sous-sol ou l'opulence affichée par certains de ses ressortissants, le Kasaï-Oriental reste pauvre et la faillite de la MIBA en 2008 ainsi que l'essoufflement du secteur artisanal ont accentué la précarité sociale et économique des populations. À l'origine de ce paradoxe apparent, un système d'impôt déficient, les prédations autoritaires des pouvoirs publics et les fraudes, innombrables. On est resté presqu'à cette économie de cueillette de l'époque de l'État indépendant du Congo dans cette région où les trous dans la brousse ou le lit des rivières sont les signes d'un système d'exploitation marqué par la violence et l'arbitraire. Ici, la convention signée en mars 2013 entre la Société congolaise d'Investissement minier (SCIM), deuxième opérateur minier de la région, et l'entreprise chinoise AFECC, semble résonner comme un espoir.

Mais le temps de la richesse du diamant semble révolu et le Kasaï-Oriental ne pourra faire l'impasse sur l'investissement de nouveaux pôles, tels que l'agro-industrie, pour espérer un développement durable et plus inclusif. Ce qui risque de reposer la question des frontières administratives établies lors de la création du district de Tshilenge en 1978.

***

De provincie Kasaï-Oriental, zoals vastgelegd door de Grondwet van 2006, ziet eruit als een land met relatief weinig vegetatie, maar met een ondergrond die rijk is aan ertsen en drie rivieren die het doorkruisen: de Lubi, de Lubilanji en de Mbuji-Mayi, waarvan de twee laatste samenvloeien in de Sankuru-rivier.

Op administratief vlak omvat de provincie het huidige Tshilenge-district en de stad Mbuyimayi. Ze is minder groot dan de stad Kinshasa en beslaat een oppervlakte zo groot als het voormalige territorium van Bakwanga, dat functioneel was in 1960. Het is de enige mono-ethnische provincie van de 26 gedecentraliseerde provincies en wordt bijna uitsluitend bevolkt door de Lubilanji-Luba. Sinds de onafhankelijkheid zijn alle politiek-administratieve entiteiten, die tijdens de koloniale periode niet versnipperd zijn, er naar een hogere rangorde opgeklommen; het voormalige territorium kreeg het statuut van district. Deze veranderingen zijn gelinkt aan de demografische verschuivingen (vóór en vooral tijdens de dekolonisatie), die aan de onverwachte oorsprong van de stad Mbujimayi liggen.

Lang voor de kolonisatie al waren de slavenhandelaars getroffen door de demografische dynamiek van de Luba-regio. Later zal de provincie uitgroeien van een slavenreservoir tot een kweekvijver van werkkrachten voor de koloniale ondernemingen. Dit, samen met de heersende ziektes en hongersnood, zal ertoe leiden dat het Luba-volk zich verspreidt over het hele land, hoofdzakelijk in de grote mijncentra langs de BCK-spoorweg en in Katanga (UMHK). Dit feit ligt aan de basis van hun uitsluiting: de dichotomie tussen de rurale en de stedelijke wereld heeft de Luba beroofd van een sociale basis die nodig was om de macht te kunnen grijpen. Hun sociale positie in de stedelijke centra, meer bepaald in de verstedelijkte randgebieden in Katanga en Luluabourg (Kananga) was duidelijk, vooreerst voor de Luba zelf, die gedwongen werden banden te smeden in de stad, als voor de 'authentieke Katangezen' en de Lulua, die etnische redenen aanhaalden voor hun economische en professionele marginalisatie. Zonder sterke drijfveren om naar hun oorspronkelijke regio terug te keren, concentreerde de Luba-elite zich op het nationale niveau, met de hele Luba-groep in haar kielzog. De situatie nam vaak dramatische wendingen. Dit was het geval bij de onafhankelijkheid, toen ze een autonoom gebied gingen vormen, met politieke autonomie, en nadien, sinds begin jaren '90, een monetair gebied met een sterke politieke identiteit.

Dit werk brengt ons naar het hart van de Lubilanji-Luba-streek, een smeltkroes van religies, waar groepen/clans met vaak complexe verhoudingen elkaar ontmoeten. De hoge bevolkingsdichtheid, die nog verscherpt wordt door de migraties en gekoppeld wordt aan de aanwezigheid van diamant in de ondergrond, leidt vaak tot verbeten grondconflicten.

Ondanks ingewikkelde socioculturele kenmerken gaan de Lubilanji-Luba prat op één en dezelfde voorvader, Nkole, en één gemeenschappelijke taal, het Tshiluba. Ze beschouwen zichzelf als een tshisa (volk) dat georganiseerd is in verschillende clans, de zogenaamde bisamba (Bakwa of Beena), Op het einde van de 19e eeuw vermeldde de kaart waarop deze bevolkingsgroepen worden gelokaliseerd, 55 groeperingen/clans, waarvan er 25 zich bevonden in de regio die overeenstemt met Kasaï-Oriental.

Het socio-economische leven van de Luba-regio is nog steeds bijna uitsluitend aangewezen op de diamanteconomie, waarbij het eerst en vooral de Forminière en nadien de Minière de Bakwanga (MIBA) waren die instonden voor de exploitatie. Sinds de onafhankelijkheid heeft de artisanale winning gestaag de overhand genomen op de industriële, een trend die al werd toegejuicht in 1960 door Albert Kalonji met zijn beroemde artikel '15 Bakwanga'. Dit werd vooral positief beïnvloed in 1982 door de nieuwe liberalisatie van de mijnvoorraden, uitgevaardigd door het Mobutu-regime, dat hiermee tegemoetkwam aan de behoeften van de politieke Luba-vertegenwoordigers. Maar ondanks de bodemrijkdommen en de weelde die sommige inwoners tentoonspreiden, blijft Kasaï-Oriental arm en het failliet van de MIBA in 2008 alsook de teloorgang van de artisanale sector, hebben de sociale en economische instabiliteit van de bevolkingsgroepen nog verscherpt. Aan de origine van deze duidelijke paradox ligt een gebrekkig belastingsysteem, de overheid die op autoritaire, quasi roofzuchtige manier te werk gaat en de niet te tellen fraudes. Deze streek is quasi blijven steken in de manuele oogstpraktijken uit de periode van de Congo Vrijstaat, in een regio waar de gaten in de brousse of de rivierbeddingen stille getuigen zijn van een exploitatiesysteem dat gekenmerkt wordt door geweld en arbitraire beslissingen. Hier lijkt het contract dat in maart 2013 werd getekend tussen de Société congolaise d'Investissement minier (SCIM) – de tweede grootste mijnexploitant in de regio en de Chinese onderneming AFECC – een hoopvolle stap in de goede richting.

***

The province of Kasai-Oriental as defined by the 2006 Constitution would, to the observer's eye, appear to have relatively poor plant cover, sitting on highly mineral-rich land and crossed by three rivers: the Lubi, the Lubilanji, and the Mbuji-Mayi. The merging of the last two rivers gives rise to the Sankuru river.

In administrative terms, it brings together the current district of Tshilenge and the city of Mbujimayi. Smaller than Kinshasa, it corresponds to the former Bakwanga territory that was operational in 1960. It is the only one of the 26 decentralised provinces to be mono-ethnic, inhabited almost exclusively by the Luba Lubilanji. Its political and administrative entities, which were spared the dismantling of the colonial era's constituent local groups, were all promoted to another level after independence, when the former territory became a district. These changes were related to population movements (before and, in particular, with decolonisation) that led to the unplanned creation of the city of Mbujimayi.

Well before colonisation, the demographic dynamism of the Luba region had already been noted by slavers. From a slave reservoir, it then became a source of manual labour for colonial endeavours. This, along with widespread disease and famine, contributed to the dispersion of the Luba people throughout the country , primarily in the major mining centres, along the BCK railway and in Katanga (UMHK). Here, then, is one of the fundamental reasons for their exclusion: the dichotomy between rural and urban deprived the Luba of a social foundation, essential to any attempt to win power. Their social position in urban centres, particularly in the urban beltways of Katanga and Luluabourg (Kananga), were apparent to the Luba themselves, who were obliged to forge ties of solidarity in the city, as well as to the ‘true' people' of Katanga and the Lulua, for whom economic and professional marginalisation was explained by ethnic reasons. With no strong incentive to return to their region of origin, the Luba elite reoriented themselves to a national role, not without dragging along the entire Luba group in this process with sometimes far-reaching consequences. This was the case during independence when they formed a zone of autonomous political management and, in the early 1990s, a monetary zone combined with a strong political identity.

This book delves into the heart of Luba Lubilanji country, an area of faiths crisscrossed by groups and clans with highly complex relationships. The high population density – worsened by migration – and the presence of diamonds in the ground have led to intense conflicts over the land.

The Luba Lubilanji, with entangled sociocultural references, claim a single ancestor, Nkole, and share a common language, Tshiluba. They identify as a tshisa (people) organized in distinct clans called bisamba (Bakwa or Beena). In the late 19th century, the map of their locations showed 55 of these groups or clans, of which 25 were found in the area corresponding to Kasai-Oriental.

The socio-economic life of the Luba region has remained almost wholly dependent on the diamond trade. Diamonds were first mined on an industrial scale by Forminière, then by the Minière de Bakwanga (MIBA). Since independence, artisanal mining has gradually supplanted industrial mining, a trend already encouraged in 1960 by Albert Kalonji with his famous article ‘15 Bakwanga' and bolstered in 1982, when mining resources were liberalized by the Mobutu regime to mollify Luba political representatives. Despite the wealth of its mineral resources and the opulence displayed by some of its residents, Kasai-Oriental remains poor. MIBA's bankruptcy in 2008 and the loss of steam in the artisanal mining sector exacerbated the social and economic instability of the people. Behind this apparent paradox lie a weak tax system, the predatory nature of public authorities, and innumerable cases of fraud. The province has remained almost unchanged from the artisanal mining practiced during the Congo Free State era, in this land where holes in the brush or riverbeds betray a mining system marked by violence and chance. Here, the agreement signed in March 2013 between the Société congolaise d'Investissement minier (SCIM) – the region's second-largest mining firm – and AFECC of China seems to be a beacon of hope.

But it appears the time of diamond-fuelled wealth is over, and Kasai-Oriental cannot miss out on investing in other fields such as agro-industry if it hopes to achieve sustainable and more inclusive development. This may reopen the question of administrative borders established during the creation of Tshilenge district in 1978.

Disponible gratuitement via ce lien

Disponible gratuitement via ce lien