Colonial cinema on the brink of the decolonisation of the Belgian Congo

In the 20 years preceding Congo's independence, Belgium increased the number of film productions in the Belgian Congo. These films had a double objective for the coloniser: to present an idealised version of a ‘modern colony’ and to ‘educate’ the Congolese population, following a paternalistic approach. The films from this period, which show a united Belgian-Congolese community living in peace and harmony, contrast with the social and political turmoil of the time, which eventually led to Congo's independence.

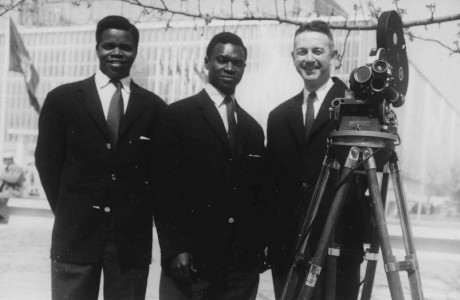

Film library of the Information Service of the General Government in Leopoldville (gouvernement général).

HP.1956.15.10273, photo J. Mulders (Inforcongo), 1950's, RMCA Tervuren ©

Colonial propaganda

From the 1940s until the independence of the Belgian Congo in 1960, colonial cinema developed under the impetus of three main actors: the Ministry of the Colonies in Brussels, the General Government (gouvernement général) in Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) and the network of Catholic missions.

The Ministry of the Colonies became the main producer and distributor of colonial films. These films were part of a colonial propaganda strategy in Belgium, which also included the press, exhibitions and, radio.

The Ministry entrusted the production of the films to Belgian filmmakers who had the required ‘profile’.

Disturbing realities such as delinquency, misery and corruption had to be avoided. Rather, the aim was to use the films as propaganda tools in order to present the Congo as a ‘model colony’ from an economic, social, medical and scientific point of view.

‘Education’ and social control of the population

In Congo, films were shown to the population in order to ‘educate’ them, to instil Christian and moral values, as well as principles of hygiene. Through the films, the coloniser also wanted the Congolese to assimilate and adopt Western morals, which were considered superior to ‘primitive customs’ (polygamy, witchcraft, ‘tribal’ dances, etc.).

The General Government, which developed its own film circuits, encouraged film screenings. From 1948 onwards, these screenings had to follow certain rules. In a practical manual entitled, Le Cinéma pour Africains (‘Cinema for Africans’, 1950), Louis Van Bever, the civil servant in charge of these issues, advocated the use of film methods and techniques adapted ‘to the mentality and intellectual level of its spectators’. He advised as follow:

- simple and short films for a basic, essentially rural audience;

- mixed films (simple films and didactic cartoons) for ‘detribalised’ spectators living in urban and industrial centres;

- didactic or recreational films for a more ‘evolved’ public, provided they are introduced and commented by colonial agents on the spot.

In the same handbook, Louis Van Bever explained that films made it possible to ‘quickly teach illiterate primitive communities how to fight disease, how to get better harvests, and how to build better houses’, without needing to read or write.

The films also aimed to maintain the coloniser’s social control over the population. Thus, the films were screened to distract and entertain the populations in large urban and industrial centres, to prevent alcoholism and to counteract the harmful effects of bars and dance halls.

Censorship

Like other colonies that feared the social impact of cinema on their citizens, the government of the Belgian Congo was careful to censor productions that were considered inadequate. It banned films that could disrupt public order and were likely to influence viewers: those that were contrary to good governance, showed gratuitous violence, offended religious convictions and decency or offended the ‘necessary prestige of the white race’, as Minister Tshoffen already wrote in a letter to the Governor General in 1933.

The administration also suggested that an official should supervise the filming by ‘questionable’ filmmakers, especially those whose work discredited the methods or results of colonial efforts with regard to public opinion abroad.

Certain themes were censored: violence, clandestine love between two ‘races’, corruption, insurrection, Whites in bad roles, etc. For example, the film Nurse Ademola was rejected because it presented the ‘overly luxurious life of a coloured nurse in England’. The film Antwerp was rejected because it showed ‘manual labour’ in the port of Antwerp. However, a good number of films fell through the cracks of the administration and were broadcasted clandestinely or privately.

Filmmakers grappling with the grim side of the colonial system

While calls for independence began to manifest themselves more openly from 1955-1956, the Belgian government was particularly cautious towards certain national and international public opinions that relayed anti-colonial criticism and attacks. The aim was to avoid sensitive subjects while emphasizing the propaganda about Belgium's ‘moral, social and political achievements’ in the Congo.

Some Belgian filmmakers openly complained about the lack of freedom in the choice of suggested themes, particularly those showing the darker side of the colonial model: poverty, urban unemployment, socio-economic inequalities, racism. For example, the filmmaker Delcourt denounced the absolute refusal of the authorities to deal with subjects such as idle or delinquent youths, or the emancipation of Congolese women.

Yet Leopoldville's growth had led to phenomena that were hardly taken into account and that the authorities preferred not to show. Delinquency, misery and corruption contrasted with grandiloquent cinematic images (Leopoldville presented as a large western city, the tourist boom, cutting-edge industries).

The role of the Congolese in film creation

Some Congolese were gradually integrated into cultural groups, which enabled them to watch certain censored films, join the Film Censorship Commission (Commission de censure cinématographique) and defend their artistic creations within specific frameworks. Nevertheless, they often remained relegated to subordinate administrative tasks (electricians, operator-assistants, assistant editors, handlers and typists). Some of them assisted a few Belgian filmmakers, but without really being able to take the initiative of directing.

Support for private entrepreneurship was also hampered. For instance, after a long quest chasing various political bodies in Congo and Belgium, Jean-Émile Malandu and Jean-Aimé Longby’s application for credit to open a cinema was declined. In April 1960, in a letter addressed to Joseph Kasa-Vubu (future president of Congo, then a member of the Collège exécutif in Leopoldville), they wrote:

Nous vous signalons, à titre confidentiel, qu’un jeune homme européen âgé de 22 ans a obtenu tout dernièrement auprès du Crédit du Colonat pour le lancement de ses affaires une somme de un million de francs et pour un Noir, on refuse catégoriquement sous prétexte qu’il n’a pas d’expérience ou encore qu’il est trop jeune […] ???

[We inform you, on a confidential basis, that a young European man of 22 years old recently obtained from the Crédit du Colonat a sum of one million francs to launch his business, but a black man gets a categorical refusal, on the pretext that he has no experience or that he is too young [...] ???]

Despite a few initiatives, notably by André Cornil, who created the African Experimental Film Centre in 1957, few Congolese were trained in filmmaking. Lukunku Sampu and Emmanuel Lubalu made commercials and news reports for Ekebo-Films. Antoine Bumba Mwaso and Dieudonné Mambula became permanent assistants to André Cornil.

This contribution is entirely based on an article published by Patricia Van Schuylenbergh, historian at the Royal Museum for Central Africa:

- Van Schuylenbergh, Patricia. 2021. « Le Congo belge sur pellicule : ordre et désordres autour d’une décolonisation (ca. 1940- ca. 1960) ». Revue d’histoire Contemporaine De l’Afrique, nᵒ 1 (janvier):16-38.

For more information, see also:

- P. Van Schuylenbergh et M. Zana Aziza Etambala (dir.), Patrimoine d’Afrique centrale. Archives Films. Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, 1912-1960, Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale, Tervuren, 2010, 351 pages.

- P. Van Schuylenbergh, « Formater les regards, décoloniser les esprits ? Éducation et transition politiques à travers les films d’archives », in M. DUMOULIN, A.-S. GIJS, P.-L. PLASMAN et C. VAN de VELDE (dir.), Du Congo belge à la République du Congo, 1955-1966, Coll. Outre-Mers, vol. 1, P.I.E. Peter Lang, Bruxelles, 2012, pp. 227-251.

Also see:

Quel Regard ! followed by an interview with Dr Chérie Ndaliko

Quel Regard ! Regard africain critique sur des films de la propagande coloniale

Colonial films were screened in Goma (DRC) in 2017 and 2018 at the Yole!Africa art centre. Young spectators, Yole!Africa members and African experts give their comments on how Europeans have filmed and represented Africans since colonial times. They question how yesterday's films would be different from those proposed today by filmmakers and NGOs. The films were chosen by Yole!Africa, on a chronological basis, one film per decade since 1910.

By Ganza Buroko. Produced by Yole!Africa and the AfricaMuseum, 2018.

Followed by an interview with Dr Chérie Rivers Ndaliko.

The excerpts of colonial films presented here come from the following films:

- Panorama Star of the Congo, anonyme, 1912

- Le fonctionnement d’une bourse de travail "La B.T.K.", Ernest Genval, 1926

- Congo, terre d’eaux vives, André Cauvin, 1939

- L’étoile au pays des fétiches, Henri Philips, 1949

- L’élite noire de demain, Gérard De Boe, 1950

- Bwana Kitoko, André Cauvin, 1955

- Le voyage royal, André Cauvin, 1955

- Fils d’Imana, la geste du Rwanda, RP.Weymeersch, 1959