Okapis

10.03.2022

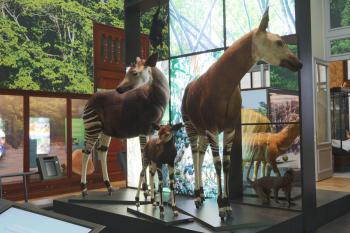

The three okapis displayed in the museum. J. Van de Voorde © RMCA

The AfricaMuseum today houses one of the largest collections of okapis (Okapia johnstoni), a species endemic to a small region in the north-east of the DR Congo, not identified by Western scientists until the beginning of the 20th century. When Congo became independent in 1960, a collection of almost 200 okapi specimens was already registered at the Belgian museum. Most of these were sent by a network of partners (military personnel, colonial agents, agronomists, missionaries, etc.) from the territory of the Congo Free State and the colony.

The three okapis on display at the museum come from two different origins. They were assembled in a “family” group in the late 1950s in a rather anthropomorphic arrangement, as the animal is actually mainly solitary.

The adult “couple” came from the Okapi Capture and Breeding Group reserve of the Colonial General Government Hunting Station (at Epulu, 500 km east of Stanleyville, now Kisangani). It was collected during a mission in 1956, led by Max Poll, curator of the museum’s Vertebrate Section:

Deux adultes, mâle et femelle, recueillis par M. Poll […] à Epulu sont choisis pour être montrés dans le pavillon congolais de l’Exposition universelle de Bruxelles (1958) avant de rejoindre les salles du Musée du Congo belge. (Van Schuylenbergh 2020 : 74)

“Two adults, a male and a female, collected by Mr Poll [...] in Epulu were selected to be displayed at the Congolese pavilion of the Brussels World’s Fair (1958) before moving to the rooms of the Belgian Congo Museum.” (Van Schuylenbergh 2020: 74)

The third okapi on display, a calf shown accompanying the couple, could be a young female hunted in the forests of the Ibina region by Lieutenant Anzélius as early as 1902 (in which case it would be No. 541 in the museum’s collections, registered in 1903).

A quest for scientific… and national prestige for European powers

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the European nations embarked on a real quest for the okapi, following a spate of descriptions of a mysterious animal from travellers to the region between 1880 and 1900.

The Englishman Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston (1858-1927), the future governor of Uganda, went in search of the okapi in 1899, but only managed to find two strips of hide (obtained from soldiers of the Force Publique). Their study nevertheless led to the adoption of the scientific name Equus johnstoni by Sclater in 1901.

In the same year, Johnston managed to obtain the whole skin of an okapi and two skulls from Karl Erikson, the commander of the Force Publique at Beni.

On the basis of these new specimens, it became clear that the animal was not a zebra but a completely new species, and Lankester changed its name to Okapia johnstoni.

Upon this scientific discovery being made, Britain and Belgium embarked on a race for specimens, whose value rose sharply. Between 1902 and 1908, the Tervuren Museum acquired no fewer than 37 specimens, including the young okapi on display (Van Schuylenbergh 2020).

A “living” symbol of the colony

Having been the subject of an international rivalry during the period of the Congo Free State, the okapi then became an important “living symbol” of the former Belgian colony. There were several attempts to capture and domesticate it. In 1919, the first live okapi was brought to Belgium as a gift to Antwerp Zoo. It only survived for 6 weeks, and its remains became part of the collections of the Tervuren Museum in accordance with the agreement between the two institutions.

It wasn’t until 1927 that the Belgian missionary, Jozef Hutsebaut (1886-1954), managed to tame the animal in the Congo, and took charge of the okapi conservation programme for the Belgian zoo.

During this period, the prestige of scientific research and the safeguarding of biodiversity remained subject to colonial propaganda. Many live okapis were shipped to European zoos (London, Rome), fulfilling a function that was as much – if not more – diplomatic as scientific. Their lives were generally short, with the animals sometimes not even surviving the journey.

Over time, however, Brother Hutsebaut became increasingly concerned about these profligate exports of okapis (and other species).

Despite this context, it was the local populations and their hunting practices, considered as poaching, who were generally blamed for endangering a species that they were not allowed to hunt, while exceptions to do so were granted to Western, mainly Belgian, scientists.

In 1956, Poll was pleased to note that okapis were “common” in the Epulu Reserve:

L’animal est tellement commun que les pièges établis au bord même de la route en capture autant que les autres plus éloignés. (Poll, 1958)

“The animal is so common that traps set at the very edge of the road catch as many as others further away.” (Poll, 1958)

Yet there were only about thirty of them there (Van Schuylenbergh 2020: 74) – hence the restrictions applied for their protection:

Bien entendu, ces captures, qui intéressent un animal jalousement protégé, se font sur un rythme discret et suivant un plan décidé annuellement. C’est grâce à elles que la mission pu se procurer un couple de ces animaux spectaculaires. (Poll, 1958)

“Of course, these captures, which concern a carefully protected animal, are carried out at a modest rate and according to an annually decided plan. Thanks to these, the mission was able to obtain a couple of these spectacular animals.” (Poll, 1958)

Appropriation of resources / cultural appropriation

As a result of growing territorial exploitation during the colonial period, the management and conservation of natural resources, including wildlife (even if this meant putting it in reserve), was an issue that also involved and benefited from a form of cultural appropriation.

Although the okapi was one of the last large mammals to be scientifically identified by Westerners, the populations of the present-day DR Congo, particularly those referred to at the time by the generic (and pejorative) term “Pygmies” (Robillard & Bahuchet, 2012), have known about the species for a long time. They called them o’api (okapi in languages of the Mangbutu-Lese group) and sometimes trapped them in camouflaged pits. Hunting this extremely shy animal is difficult, and so traditional techniques and skills continued to be used to capture these animals during colonial rule.

Poll describes such a hunt:

La chasse est ici particulièrement difficile, aussi sont-ce les pygmées (sic) qui opèrent en capturant les animaux au filet ou au piège.

L’okapi ne se chasse pas mais se prend dans les fosses creusées à peu de distance de la route où la bête tombe pendant la nuit. Elle est ensuite ingénieusement conduite vers le camion qui l’attend au bord de la route par le chemin des étroit couloir de sticks qui ne lui donne pas d’autre issue. (Poll, 1958)

“This kind of hunting is particularly difficult, so it is the Pygmies [sic] who operate by catching the animals with nets or traps.

The okapi is not hunted but caught in pits dug a short distance from the road which the animal falls into during the night. The animal is then carefully led to the waiting truck at the side of the road through a narrow corridor of sticks which gives it no other way out.” (Poll, 1958)

Perhaps more than for any other animal, local people played a key role in the “discovery” of the okapi by Europeans. The attribution to the species of the names of their Western “discoverers” are thus sometimes criticised for reflecting and conveying a biased scientific narrative, contributing to the invisibility of existing knowledge and skills.

Decolonising the natural science collections?

In the museum, the label for the okapi display does not contain any information on their provenance or even on their entry into the institution’s collections. The inventory numbers of the three specimens are not mentioned.

The only information included is “Danger of extinction: endangered, 2018”. Reduced to a single factual, scientific and contemporary statement, the information on the three okapis omits all information about the historical origin of the display, presenting the specimens as interchangeable “objects”.

Despite the possible difficulties in establishing a definite identification with the registers, provenance research on the zoological collections largely overlaps with the history of the collections (networks, circuits) in other departments of the institution, including Cultural Anthropology. If only in this respect, it appears to be equally essential to our understanding of the current problems linked to the overwhelming presence of various forms of Congolese heritage in Belgium, in the complexity of their whole.

Text compiled from a draft by Agnès Lacaille based on specific research and a synthesis of the data below.

SOURCES

Interviews and correspondence: Garin Cael, Emmanuel Gilissen, Tine Huyse, Jacky Maniacky, Patricia Van Schuylenbergh.

Archives:

Zoology Section: “Rowland Ward” file, M. Poll files.

Bibliography:

- Marine ROBILLARD and Serge BAHUCHET, “Les Pygmées et les autres : terminologie, catégorisation et politique”, Journal des africanistes [online], 82-1/2 | 2012, published online on 10 May 2016, viewed on 26 January 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/africanistes.4253

- Sabine Cornelis “Le colonisateur satisfait ou le Congo représenté en Belgique (1897-1958)”, La mémoire du Congo, le Temps colonial, MRAC 2005, pp. 159-169.

- Maarten Couttenier, Si les murs pouvaient parler, Tervuren, MRAC, 2010, pp.

- J. FRAIPONT, “Okapia”, in Annales du Musée du Congo, Zoologie, série II, Contributions à la faune du Congo, n° I, Tervuren, Musée du Congo, 1907.

- Huyse Tine, Opening van het vernieuwde AfricaMuseum, EOS Wetenscahap.

- Nick De Meersman, Natuur is eigendom van de staat. Gebruik van natuurlijke bronnen en wilde dieren in de koloniale wereld, History Master’s thesis, University of Ghent, 2013.

- Max Poll, “Une mission zoologique taxidermique du musée royal du Congo Belge (1956)”, Congo-Tervuren, 1958, vol. 3-6, pp. 35-40

- Pouillard Violette, 2020. “Animaux et environnement: conserver était-ce protéger?”, in Le Congo colonial. Une histoire en questions, Tervuren, AfricaMuseum / Waterloo, RL, 2020, pp. 385-396.

- Patricia Van Schuylenbergh, “Sur les traces de l’Okapi”, Wonderkamer, Gewina édition, n° 1, June 2020, pp. 72-74.

- Patricia Van Schuylenbergh, De l’appropriation à la conservation de la faune sauvage. Pratiques d’une colonisation: le cas du Congo belge (1885-1960), doctoral thesis, Louvain, 2006.

Others:

- Ecsite webinar and article

- Süess Léonie, paper presented at the Provenance Globale symposium, Lausanne, Palais de Rumine: Léonie Süess (palaisderumine.ch)

- Blog by Annick Debaillie (together with Professor Morris):

http://museummenagerie.blogspot.com/

http://home.scarlet.be/~ad041677/RWard_RMCA/cabinet.html

The information contained in this article is mostly based on resources available at the museum (archives, publications, etc.). The specimen's biography, therefore, can still be developed further. Do you have any comments, information or stories to share? Please contact us: provenance@africamuseum.be.

In the framework of the Taking Care project.