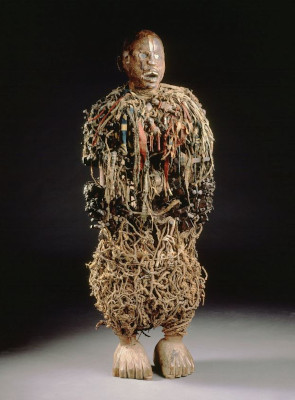

Catalogue number EO.0.0.7943

December 2020

Some of the objects in the collections of the AfricaMuseum are controversial for their violent colonial history. In recent years, therefore, the museum has sharpened its focus on provenance research, which examines the history of objects in collections. Where the objects come from and under what circumstances they were collected are central questions. Maarten Couttenier, historian of the AfricaMuseum, wrote a scientific article about a kitumba sculpture. In the late nineteenth century, in 1878, the statue was stolen by Belgian tradesman Alexandre Delcommune from Congolese chief Ne Kuko. Three times already it has been reclaimed. The first request for return was made in 1878 by Ne Kuko himself. The second request was made by President Mobutu, almost a hundred years later, when in 1973 he asked for the return of all 200 artefacts from a travelling exhibition in which the kitumba statue was also on display. The third time was in 2016 in a conversation between the researcher and a descendant of Ne Kuko, chief Alphonse Baku Kapita. The object is kept in the AfricaMuseum under catalogue number EO.0.0.7943.

photo Plusj, RMCA Tervuren ©

If there is a discussion about restitution in Belgium today, it will also be about the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren. The RMCA, both museum and scientific research centre, manages extensive collections of artefacts, mainly from Congo, Rwanda and Burundi, African countries formerly colonised by Belgium. Certain objects have an appalling history. RMCA historian Maarten Couttenier examines the history of object EO.0.0.7943.

The violent past of the kitumba statue

Under inventory number EO.0.0.7943 a wooden statue from Congo is registered in the RMCA catalogue, the current repository of this statue full of metal nails dating from the first half of the nineteenth century. Maarten Couttenier's provenance research reveals how this statue was captured with certainty by a Belgian in violent and unbalanced colonial conditions.

The statue was originally owned by Ne Kuko - one of the nine great chefs of Boma, in the western part of the DR Congo. The Belgian rubber and ivory trader Alexandre Delcommune had an economic conflict with the leader. In his memoirs, the Belgian wrote how the conflict arose after the drought of 1878 in Congo. The extreme weather conditions had caused a loss of income and to overcome this, the nine kings decided to introduce a tax increase on their trade routes. This was seen as intolerable by traders such as Delcommune. When the local chiefs formulated that 'the whites could also return home if they did not like it', it was seen as an outright declaration of war. The Belgian businessman ordered his mercenary army to attack the insurgents during the night and "teach them a lesson". During a nocturnal raid, houses of Ne Kuko's village were set on fire. Presumably the statue was left behind in these violent circumstances. This is how it came into the hands of Delcommune, who was well aware of its value. In the past he himself had appealed to the object in return for payment. He therefore called it a "hostage, more important still than a human hostage".

Three requests for the statue's return

The kitumba statue functioned as a famous, supernatural 'fetish', a 'God'. Whoever possessed the object was respected and feared. That is why chief Ne Kuko demanded it back after the attack in 1878, but Delcommune refused and travelled with the statue to Belgium in 1883, where it would stay up until this present day.

As far as is known, a second request for return was made in 1973 by President Mobutu Sese-Seko (1930-1997). He dreamed of having his own 'Tervuren' in Kinshasa, where the lost African art could finally be seen by Africans themselves. The catalogue of the travelling exhibition Art of The Congo, had made Mobutu aware of 200 objects, originating from his country, but owned by the former coloniser. During his famous UN speech in New York in 1973, the Zairean president demanded these 200 objects back from Belgium. Former RMCA director Lucien Cahen sent 144 pieces from Tervuren, only one of which was exhibited in Art of the Congo. Ne Kuko's sculpture remained in Belgium.

In 2016, chief Alphonse Baku Kapita, a descendant of Ne Kuko, told the historian Maarten Couttenier that he would also want the nail statue back so that it could once again fulfil its ritual role in his community.

In need of a legal framework on restitution

In Belgium, there is still no legal framework for the restitution of objects and human remains that have been unlawfully acquired. Compared to some of its European neighbours, Belgium is running behind. In 2020, the newly appointed State Secretary in charge of Science Policy pleads in his policy paper for the development of a restitution policy for works of art and human remains. To this end, he wants to set up a working group with all stakeholders.

In its restitution policy, the RMCA commits itself to further provenance research for the thousands of objects in its collection of which nothing is known yet. In this way, the various interested parties can find out which objects have been obtained illegally and by force (looting, hostage-taking and grave robbery) or in unequal colonial power relations. The museum also recognises "that it is not normal for such a large part of Africa's cultural heritage to be located in the West, when the countries of origin are actually the moral owners of it". The RMCA is actively discussing its restitution policy with the Congolese and Rwandan institutions of national museums.

This contribution is based on an article by Maarten Couttenier, historian of the Royal Museum for Central Africa:

Couttenier, M. (Volume 133-2 (2018)). EO.O.0.7943. BMGN - Low Countries Historical Review, 79-90.

> Also read this article on the provenance of this statue