Nkisi Nkonde Statue

08.10.2021

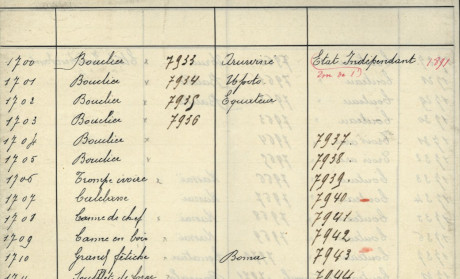

- Inventory number EO.0.0.7943

- Wood (Canarium schweinfurthii) and other materials

- 19th century

- Property of Chief Ne Kuko, one of the nine kings of Boma

- Village of Kikuku, Boma region, Bas-Congo, DR Congo

- Looted by Alexandre Delcommune following a punitive expedition, end 1878

- Kept by Delcommune in his post/warehouses in Boma

- Its return was demanded by Ne Kuko at the end of 1878 (before his conflict with and defeat by Jouca-Pava)

- Brought to Belgium by Delcommune in 1883

- Given by Delcommune to the Association Internationale Africaine, probably around 1883

- Exhibited in Antwerp in 1885

- Given by the Congo Free State to the Halle Gate Museum in 1891

- Moved in 1906 to the Royal Museums of Art and History in the Cinquantenaire Park

- Given to the Museum of the Belgian Congo (now AfricaMuseum) in 1912

A power figure...

Belgian trader Alexandre Delcommune (1855-1922) took this statue from the area around Boma during an attack against Chief Ne Kuko in 1878.

At that time, a few Europeans, mainly Portuguese, were working for various trading companies from several Western states, and were established in this region of the Congo estuary.

Delcommune arrived in Boma in 1875 in the employ of the French ivory and rubber trading company Lasnier, Daumas, Lartigue et cie (which became Daumas, Béraud & cie in 1879).

In his memoirs, Delcommune describes the economic conflict behind the war against the nine kings of Boma, during which he looted this statue.

At this time, the end of the slave trade, the commercial competition over inland territories and a prolonged drought in Congo since 1872, had combined to cause a sharp decline in trade flows and therefore a loss of revenue for the Congolese intermediaries between Mayumbe and the Bas-Fleuve district. In response, the nine chiefs of Boma decided to increase taxes on their trade routes.

This decision, which ran against an earlier agreement of 1872, was deemed intolerable by the European traders. Despite the pressure exerted on them, the chiefs of Boma nevertheless stood their ground.

"Les rois chargèrent nos envoyés de nous dire que la terre leur appartenait, qu’ils étaient seuls maîtres chez eux, que si les blancs n'étaient pas satisfaits, ils n’avaient qu’à s’en retourner d’où ils étaient venus."

"The kings charged our envoys to tell us that the land belonged to them, that they alone were masters of their land, and that if the whites were not satisfied, they could simply go back from whence they came." (Delcommune 1922: 93)

The European traders saw this response as a declaration of war and decided to carry out a punitive attack on the chiefs. Eight of the nine chiefs of Boma were attacked at night by European agents assisted by mercenaries (known as Kroumen). Delcommune led the offensive against Ne Kuko, during which homes were burned "so as to illuminate the scene and stoke fear among the besieged". The assault took the inhabitants of Kikuku village totally by surprise and sparked panic, forcing them to abandon this sculpture as they fled.

Delcommune knew about this power figure, which he described as a "war fetish", and had even invoked it to find six of his employees accused of stealing from his warehouses.

"Je connaissais ce fétiche depuis longtemps et je savais la réputation très grande dont il jouissait à vingt ou trente lieues à la ronde. J’en fis l’expérience moi-même dans des circonstances curieuses qui méritent d’être racontées et qui montrent la foi qu’ont les indigènes dans certains de ces dieux."

"I had long known of this fetish and I knew it bore a strong reputation for twenty or thirty leagues around. I had had experience of it myself in peculiar circumstances that are worth telling and which demonstrate the faith that the indigenous people have in some of these gods." (Delcommune 1922: 96)

In using the power figure, he sought – successfully – to get the population to denounce the fugitives.

When he took it, therefore, Delcommune knew perfectly well that he had taken an extremely powerful "hostage".

"J’avais la certitude que la prise de ce dieu fameux aurait un effet considérable sur la suite des évènements qui se déroulaient en ce moment."

"I was certain that seizing this famous god would have a considerable effect on the further course of events occurring at that time." (Delcommune 1922: 100)

Indeed, as soon as discussions to end the conflict were initiated by the kings of Boma, Ne Kuko asked for the statue to be returned to him. However, Delcommune refused, believing that the statue was not part of the current negotiations and that, as a spoil of war, it was for him alone to decide on a possible "repurchase" when the time came.

Ne Kuko protested against this attitude, and Delcommune made threats against him.

"Le roi Né Cuco demanda que le grand fétiche lui fût rendu, ce à quoi je m’opposai formellement, la chose n’étant pas prévue dans la palabre.

Le fétiche étant une prise de guerre, m’appartenait ; je ne traiterai de son rachat que lorsque j’en jugerais le moment opportun.

Le roi Né Cuco se fâcha à tel point que je finis par lui dire que s’il voulait son fétiche, il n’avait qu’à venir le chercher chez moi, mais que je ne lui conseillais pas de tenter l’aventure."

"King Né Cuco asked that the grand fetish be returned to him, which I clearly opposed, as the matter was not up for discussion.

As the fetish was a spoil of war, it belonged to me; I would only deal with its repurchase when I deemed the moment opportune.

King Né Cuco became so angered that I ended up telling him that if he wanted his fetish he should simply come to my house and get it, but I advised against his attempting it." (Delcommune 1922: 103)

According to Delcommune, "this war [...] permanently damaged the prestige of the kings of Boma and considerably bolstered the authority of the Europeans." It also sparked conflict between King Ne Kuko and Prince Jouca-Pava, who was minister (mambouc) to the nine kings but also the representative of the French firm that Delcommune managed, within the Congolese community:

"[…] quelques mois plus tard, un conflit armé [éclata] entre le roi Né Cuco et Jouca-Pava, que le premier accusait d’être la cause de l’insuffisance de droits de passage des caravanes du Mayumbe et de la non-remise du fétiche dont je n’avais pas voulu me dessaisir, malgré la riche rançon qu’en offrait le roi.

Jouca-Pava battit les hommes de Né Cuco lui incendia sa résidence et l’obligea à payer un tribut de guerre considérable."

"[...] a few months later, an armed conflict [broke out] between King Né Cuco and Jouca-Pava, whom the former blamed for the insufficient duties on caravans from Mayumbe and for the non-return of the fetish that I had not wanted to relinquish, despite the hefty ransom the king was offering.

Jouca-Pava beat Né Cuco's men, set his home on fire and forced him to pay a sizeable war tribute." (Delcommune 1922: 103-104)

Bolstered by this ruthless victory, Delcommune refrained from returning the statue in the four years that followed. He took it to Belgium when he returned in May 1883 (Couttenier 2018 & 2020).

In Brussels, Delcommune was received with respect by Maximilien Strauch, Secretary General of the Association Internationale Africaine (AIA). Under a humanitarian guise, the purpose of this organisation created by Léopold II was to conquer territories in Africa.

Delcommune gave the Ne Kuko statue to the AIA, before returning to Congo in October 1883 on behalf of the Association Internationale du Congo (AIC). This organisation was also created by Léopold II to replace the Comité d’Étude du Haut-Congo (CEHC) whose first agents (including Henry Morton Stanley) Delcommune had seen arrive in Boma.

From that time on, Delcommune decided to join the Belgian King's company.

"Ce fut à cette époque et sur les conseils de mes nouveaux amis, que je résolus, moi aussi, de travailler à la grande œuvre due à l’initiative du Roi des Belges, et malgré l’admirable santé que j’avais et la belle position que j’occupais, je résolus de rentrer en Europe et de me mettre à la disposition du Comité d’Etudes du Haut-Congo."

"It was at this time, and on the advice of my new friends, that I resolved to work on the great undertaking of the King of the Belgians, and despite my admirable health and my fine position, I resolved to return to Europe and to make myself available to the Comité d’Etudes du Haut-Congo." (Delcommune 1922: 145)

As a trading post manager and the longest-established Belgian in Boma, Delcommune would certainly not have been under any illusions as to what the company was fronting.

Stanley himself admitted that so-called geographic societies and trade companies were not just looking to expand their geographic knowledge and trade prospects, but also to serve the political interests of their governments (Couttenier 2020: 49).

When Delcommune joined in 1883, the AIA and the AIC had already officially announced their participation in the Antwerp World's Fair planned for 1885. It was most likely amidst this emerging colonial propaganda that Delcommune donated the statue.

Further crimes against the kings of Boma

Delcommune’s role against the kings of Boma was far from over. On the contrary, the AIC wanted to draw on his experience to pursue a strategy that was no longer content merely to demonstrate commercial or geographic (or even humanitarian) purposes, but sought to acquire sovereign rights over the territories concerned.

"Ce fut en avril 1884 que je reçus les premières instructions de Bruxelles, instructions datées du 1er février, faisant connaitre confidentiellement les vues politiques de l’AIC.

L’objet de ces instructions était de jeter les premières bases du futur Etat, par l’obtention de la soumission des roitelets indigènes."

"It was in April 1884 that I received the first instructions from Brussels, instructions dated 1st February, confidentially revealing the political views of the AIC.

The object of these instructions was to lay the initial foundations of the future State, by securing the submission of the indigenous kinglets." (Delcommune 1922: 160)

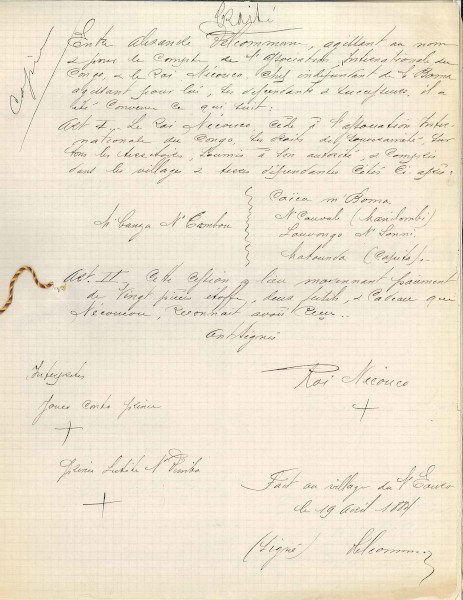

Delcommune therefore resumed contact with the nine chiefs, whom he invited to the village of N'Eourou (home of King Ne Oro) on 19 April 1884 and persuaded to sign nine treaties relinquishing their sovereignty. The Archives Africaines of the Belgian Federal Public Service Foreign Affairs holds the originals and copies of these documents which were signed with a cross by the region's nine kings. King Ne Kuko was one of the signatories:

Transcription:

Traité

Entre Alexandre Delcommune, agissant au nom & pour le compte de l’Association Internationale du Congo & le Roi Nécouco chef indépendant de M’Boma agissant pour lui ses descendants et successeurs, il a été convenu ce qui suit :

Art. I. Le Roi Nécouco cède à l’Association Internationale du Congo les droits de souveraineté sur tous les territoires soumis à son autorité, y compris (?) dans les villages & terres dépendantes cités ci-après :

M’banza N’Cambou (?) : Caïeu m’Boma, N’Couvale (Manidombi), Louvongo N’Sonni, Matunda (Capita)

Art. II. Cette cession a lieu moyennant paiement de vingt pièces d’étoffes, deux fusils, & cadeau que Nécoucou reconnait avoir reçu.

Ont signé

Roi Nécouco X

Interprètes :

-Jouca Couto prince X

- prince Lutete (?) X

Fait au village de N’Eourou

Le 19 avril 1884

(signé) Delcommune

Treaty

Between Alexandre Delcommune, acting in the name and on behalf of

the Association Internationale du Congo, & King Nécouco, independent chief of M’Boma acting on behalf of his descendants and successors, it is agreed as follows:

Art. I. King Nécouco relinquishes to the Association Internationale du Congo the sovereign rights to all the territories under his authority, including (?) in the dependent villages & lands cited below:

M’banza N’Cambou (?): Caïeu m’Boma, N’Couvale (Manidombi), Louvongo N’Sonni, Matunda (Capita)

Art. II. This relinquishment is in return for payment of twenty pieces of fabric, two rifles & gift which Nécoucou acknowledges receiving.

Signed

King Nécouco X

Interpreters:

-PrinceJouca Couto X

- Prince Lutete (?) X

Signed in the village of N’Eourou

on 19 April 1884

(signed) Delcommune

Delcommune himself confesses in his memoirs that he misled the kings of Boma, boasting a few lines earlier that he had "inspired their every confidence". (p. 163):

"Il serait grotesque de ma part d’affirmer que je mis ces rois au courant de tous les privilèges que comportent les droits de souveraineté […]."

"It would be grotesque of me to assert that I informed these kings of all the privileges that the rights of sovereignty entailed [...]." (Delcommune 1922: 165)

The nine kings of Boma, supported by the Portuguese traders, quickly tried to break free of these commitments by stoking European rivalries. This resistance seems moreover to have revolved around Ne Kuko. It was in his village that on 5 June 1884, the first large public meeting was held "to make declarations about the rights of sovereignty that these princes [kings] had over the territories they governed." (Delcommune 1922: 168).

Nevertheless, the Boma kings failed to escape the grip of Belgium, which was further strengthened by recognition of the Congo Free State (CFS) by the Western powers in 1885.

From one collection to another

During Delcommune's second stay in Congo, the Ne Kuko statue was moved from the AIC collections to the collections of the newly formed EIC, which remained stored in the stables of the Royal Palace in Place du Trône, Brussels (Van Schuylenbergh 2020: 130).

The Ne Kuko sculpture was exhibited at the Antwerp World's Fair in 1885, during which it visibly drew the attention of visitors and commentators to the event. But when the statue was given by the EIC to the then Halle Gate Royal Museum of Arms, Armour, Antiquities and Ethnology, its story was lost for a while among the various Congo collections that filled the rooms. The object was then moved in 1906 to the new premises at the Parc du Cinquantenaire. Due to lack of space and suitable display arrangements, the ethnographic and African collections spent several years in storage. In 1912, the Congo pieces were sent to the Museum of the Belgian Congo (now AfricaMuseum) in Tervuren, where all the Belgian State's collections from its "new" colony were held.

According to Maarten Couttenier, it is possible that the statue was also exhibited at the Antwerp exhibition in 1894 with another very similar-looking sculpture that was then given by the EIC to the Leiden Museum (where it remains to this day). Several of these large Yombe power figures, therefore, were taken by EIC agents (or their forerunners) around that time, raising questions over the circumstances of this “seizure” of heritage items in the context of a hegemonic conquest of power.

... and family archives

When Delcommune returned to Belgium in 1883, bringing the Ne Kuko statue with him, he also brought with him a three-year-old girl called Adèle, born in Boma in 1880 through his marriage with Mabenjia, one of the three daughters of Prince Jouca-Pava.

"Ce fut en mai 1883 que je repris le chemin du pays natal. Je l’avais quitté neuf ans auparavant. J’étais accompagné de la petite fille âgée de trois ans que j’avais eue avec la fille de Jouca-Pava. Un jeune boy de dix ans que j’amenai pour la soigner, m’accompagnait également."

"It was in May 1883 that I returned to my home country. I had left it nine years earlier. I was accompanied by the three-year-old girl that I had had with the daughter of Jouca-Pava. A ten-year-old boy that I brought to look after her, also accompanied me." (Delcommune 1922: 148-149)

This marriage took place after an open conflict between Jouca-Pava and Delcommune. While Jouca-Pava's agreement to this marriage was certainly forced, as Delcommune's account shows, Mabenjia's consent is not even mentioned.

AFROPEA Gallery

In the museum's Afropea Gallery, you can see a studio portrait of Adèle Delcommune (1880-1933) by famous photographer Alexandre, no doubt taken on occasion of her marriage, which took place in Brussels on 20 June 1905.

Another later photograph shows her husband, Eugène Peeters (1880-?), in 1954.

The final family portrait is of their son William Peeters (1908-1973). He was Alexandre Delcommune's grandson, the young Willy to whom Delcommune dedicated the first volume of his memoirs Vingt années de vie africaine. Récits de voyages, d’Aventures et d’Exploration au Congo belge. 1874-1893 [‘Twenty years of African life: Tales of travel, adventure and exploration in the Belgian Congo’], published in 1922:

A mon petit-fils Willy

Agé aujourd’hui de quatorze ans.

Pour l’engager à parcourir le monde comme l’a fait son grand-père.

L’homme, qui n’a pas voyagé, non seulement ne peut se faire une idée des beautés prodigieuses que la nature étale sur la surface du globe, mais encore est incapable de comprendre l’humanité.

To my grandson Willy.

Fourteen years old today.

To encourage him to travel the world as his grandfather has done.

Any man who has not travelled, not only cannot imagine the prodigious beauties that nature lays out across the surface of the globe, but is also incapable of understanding humanity.

Reading this work today is enlightening as an emblematic testimony of the violent acquisition of material goods, including cultural and heritage items, as part of an aggressive economic strategy, but also of the fate that sometimes befell young women and children.

The power struggle between Europeans and Africans, the inequity of which varied according to the personalities of those involved, continued to grow as the European territorial occupation tightened its grip over the years, an occupation that clearly sought to subjugate the African populations (formalised by the signing of the treaties to relinquish sovereignty). The fate of Jouca-Pava, Adèle's grandfather and whose tragic end is described by Delcommune (Delcommune 1922: 86), illustrates both the drama of shattered destinies, and the family bonds woven in the shadow of the History that then developed between Congo and Belgium.

The photographs of Adèle and William Peeters were given to the museum in 1954 by Eugène Peeters (Delcommune's son-in-law) who is pictured "sitting in his father-in-law's favourite armchair" in the third image. The latter was taken during a visit by Frans M. Olbrechts (the then Director of the Museum of Tervuren) to Eugène Peeters, at the family villa in Spa, on 7 July 1954.

A photographic report (see below) was also produced on this occasion by René Stalin, a photographer working for, among others, the colonial propaganda agency, Inforcongo.

Mongonganita Villa

In 1909, Delcommune had a villa built (of which only the stable building survives today) in Spa. The villa's name, Mongonganita, is a clear link with the owner's African past, referring to one of the names he was given during his first stay in Bas-Congo:

"Pendant ces neuf années consécutives de séjour sous les tropiques, de 1874 à 1883, j’avais été baptisé quatre fois par les indigènes, c’est-à-dire que j’avais changé trois fois de surnom. Le premier qui était tout indiqué ‘Long nez’, fut suivi de ‘Grand Tireur’, puis du ‘Chasseur d’hippopotames’ ; et enfin le dernier ‘Mongongo’, qui veut dire ‘celui qui aime les femmes’, me fut donné par suite d’un petit incident que je raconterai pour la curiosité du fait."

"During those nine consecutive years spent in the tropics, from 1874 to 1883, I was baptised four times by the indigenous people; in other words, I changed names three times. The first was perfectly suited, "Long nose", which was followed by "Great Shooter", then "Hippopotamus Hunter". The last, "Mongongo", which means "he who loves women", was given to me following a little incident that I will recount for its peculiarity." (Delcommune 1922: 145)

However, it is difficult to translate the term Mongonganita literally: in Lingala, "mongongo" means "throat, voice", and "anita", aside from being a female name, is difficult to interpret.

Laman's Kikongo-French dictionary (1936), however, reveals that, in Kikongo, "mungonga" is the "name of certain Whites (from Europe)" but, more especially, that "mungongoanyeka means "to have a supple body, supple loins". Mongonganita may be a deformation of the expression by Delcommune, which would shed a somewhat less chivalrous light on the explanation of this nickname recounted by Delcommune in his memoirs.

Regardless of the relevance of this translation, Mongonganita Villa was very clearly designed to hold Delcommune's African souvenirs. In the billiard room, the rich display of the collection of Congolese objects also includes animals - as well as the reconstruction of an imaginary hunting trophy (n° 623) – and photographs (a display stand can be seen in n° 621) (Van Schuylenbergh 2020: 73-75).

Other objects in the "Delcommune Collection"

Despite the extensive scale of the displays in Mongonganita Villa, the collections that came to the museum from Delcommune's heirs and descendants amount to just 38 objects, including one musical instrument (a Luba whistle). One of these objects, a sculpted ivory pendant from Katanga, joined the collections of the Institute of the National Museums of Zaire in 1978.

The collection, sold in 1958 by William Peeters, Delcommune’s grandson, primarily comprises small utilitarian objects of prestige for personal use:

- a dozen sculpted ivories from Katanga;

- eight Kuba cups;

- five ivory bracelets;

- three statuettes from the Bas-Congo region;

- two Kuba pipes, one of which is of excellent quality (EO.1958.6.9 - published in the catalogue Trésors cachés, n°139);

- a few tools.

Most of these objects were probably collected during his third and fourth stays since they mostly come from regions that Delcommune travelled through during that period.

None of these pieces are currently displayed in the museum's galleries, but, aside from the three family portraits mentioned above, there is another photographic reproduction in the permanent exhibition that refers to Delcommune.

Landscapes and Biodiversity Gallery

This photograph, signed by Delcommune, is entitled "Souvenir de chasse" (hunting souvenir in English). You will find it presented on the plate for the stuffed hippopotamus exhibited in the Landscapes and Biodiversity Gallery.

This image gives an idea of Delcommune's activities during his fourth stay in Congo. This was the second trip he made for the Compagnie du Congo pour le Commerce et l'Industrie (C.C.C.I.), an organisation that employed him from 1887 and accepted him onto its Board of Directors in May 1889 on his return from his first assignment concerning the trade prospects of a railway in Haut-Congo.

On this second trip, however, Delcommune was to lead an expedition in Katanga.

He left Europe in mid-1890, accompanied by mining engineer Norbert Diderrich, among others. The economic and political stakes of this mission are reflected by the extreme distances covered and the human toll of the expedition, which faced numerous episodes of conflict and famine during its travels.

This photograph of Delcommune posing proudly next to a hunting trophy of 13 hippopotamus heads arranged in a pyramid was taken on 13 July 1891 on the Lomami River, above the village of Makoa.

One of the images of Mongonganita Villa (n° 619) shows another photograph of this hippopotamus hunt, over the fireplace in the billiard room. This is the counterpart that is essential to understanding the photograph exhibited in the museum.

These photographs were both published in the second volume of Delcommune's work entitled Vingt années de vie africaine. Récits de voyages, d'aventures et d'exploration du Congo Belge, 1874-1893 (image 1 / image 2).

The photographs differ in iconographic tone. The photograph depicting Delcommune and the hippopotamus heads has gone down in history and has often been presented as a symbol of the destruction of wildlife carried out in Congo, "bolstered by the caption of the author showing the heads of game: An uncommon hunting trophy (Delcommune 1922: 128), along with his long note justifying to a certain extent the easiness of the act undertaken on dry land, while water hunting poses greater dangers," (Van Schuylenbergh 2020: 41-42).

But the other image no doubt gives a more accurate depiction of the exceptional nature of this slaughter of 13 hippopotamuses in record time (2½ hours), which drew a crowd of African spectators:

"Jamais je n'ai vu encore gens plus impressionnés que les indigènes des villages les plus rapprochés, qui étaient tous accourus à mon retour de cette chasse. Ils n'osent plus m'approcher, et la femme qui sert de guide se roule à mes pieds et me baise les mains."

"I have never seen people as impressed as the indigenous people from the nearest villages, who came running on my return from the hunt. They no longer dared approach me, and the woman acting as a guide bent at my feet and kissed my hands." (Delcommune 1922: 128)

This photograph also illustrates the issue of providing food for these massive expeditions in an uncertain context:

"Il semble, néanmoins, que les repas en viande constituent parfois un luxe dans les expéditions qui se nourrissent surtout sur le dos des populations des régions traversées et dépendent ainsi du bon ou mauvais état de santé des productions vivrières locales. Durant son expédition au Katanga en 1891, Alexandre Delcommune (1855-1922) au service de la Compagnie du Congo pour le Commerce et l'Industrie (C.C.C.I.) narre les aléas du voyage durant lequel alternent des périodes de franches famines avec des festins parfois ‘pantagruéliques’ qui dépendent de ce qu'il peut alors trouver en gibier de chasse. Sur le Haut-Lomami, Delcommune et son adjoint Diderrich abattent pendant deux heures et demi, treize hippopotames qui fournissent plus de quinze mille kilos de viande aux quatre cents suiveurs africains et dont une partie est échangée avec les hommes de Kasongo Kalombo afin d'annoncer sa venue pacifique dans son territoire. Si l'ampleur de cette chasse était exceptionnelle, les hippopotames ne sont pas rares et demeurent la principale ressource en viande du voyage, outre le gibier traditionnel, antilopes, zèbres, oiseaux."

"Nevertheless, it seems that meat was sometimes a luxury on these expeditions, which fed mostly off the backs of the populations of the regions they travelled through and depended therefore on the good or poor state of health of the local crops. During his expedition to Katanga in 1891, Alexandre Delcommune (1855-1922), in the service of the Compagnie du Congo pour le Commerce et l'Industrie (C.C.C.I.), narrates the vagaries of the journey which alternated between periods of major famine and sometimes 'gargantuan' feasts, which depended on whether they could find hunting game. In Haut-Lomami, Delcommune and his assistant Diderrich killed, in the space of two and a half hours, thirteen hippopotamuses, which provided more than fifteen thousand kilos of meat for the four hundred African followers, and a portion of which was traded with the men of Kasongo Kalombo in order to announce their peaceful arrival in their territory. Although the scale of this hunt was exceptional, hippopotamuses were not scarce and remained the main source of meat on the journey aside from traditional game, antelopes, zebras, birds. It helped, to a certain extent, compensate for the periods of famine during the expedition which decimated more than half of the camp's men." (Van Schuylenbergh 2020: 41-42)

After hunting opportunities such as this one, the men would sometimes carry loads of more than 24 kg of meat.

Resolving these difficulties, particularly food supplies, was not always possible. Out of the 670 men that left on Delcommune's expedition, 500 had lost their lives by the time it ended in February 1893.

As part of his research, historian Maarten Couttenier met with the current chiefs of the region of Boma, Alphonse Baku Kapita and Madelaine Tsimba Phambu. In this podcast, he talks about his meeting with Chief Alphonse, the current chief of the village of Kikuku (podcast in Dutch):

Text compiled from a draft by Agnès Lacaille based on specific research and a synthesis of the data below.

SOURCES

Interviews, correspondence (emails): Christine Bluard, Bambi Ceuppens, Maarten Couttenier, Jacky Maniacky, Hein Vanhee, Patricia Van Schuylenbergh.

Archives:

- AGR: Africa Personnel Records, record SPA/DG/767, p. 201, A. Delcommune ; Marital status, marriage record

- RMCA, Ethnographic section, acquisition record: Royal Museums of Art and History; Eugène Peeters; William Peeters.

Bibliography:

- Bontinck F., Boma sous les Tshinus, Zaïre-Afrique 135 (1979), pp. 295-314

- Couttenier M., Le Congo à Anvers, avant Berlin et Leyde, 100x Congo, exhibition catalogue, Antwerp, MAS, 2020, pp. 46-57.

- Couttenier M., EO.0.0.7943, BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review, vol. 133-2, 2018, pp. 79-90

- Delcommune A., Vingt années de vie africaine. Récits de Voyages, d’Aventures et d’Exploration au Congo belge, 1874-1893, Brussels, Vve F. Larcier, 1922. Volume I / Volume II

- Haulleville A. (Baron de), C’est dans un grenier à foin que Léopold II réunit les premières collections du Musée du Congo belge, Les Cahiers Léopoldiens, issue of 15 December 1958 to 15 January 1959, pp. XXIX and XXX.

- Lauro A., Des femmes entre deux mondes : ‘ménagères’, maîtresses africaines des coloniaux au Congo Belge, proceedings from the conference Savoirs de genre / quel genre de savoir ?, Brussels, Sophia, 2005, pp. 206-222.

- Le Congo illustré, vol. I, fasc. 1, 1892, (ill. January: L’école des inkimbas du village de Nékuku, based on a photograph by Mr Shanu, a photographer in Boma)

- Luwel M., Le Musée du Congo du Léopold II. Des combles des écuries royales aux somptueuses salles de Tervuren, Revue Congolaise Illustrée, XXX, 1958, 6, pp. 13-16.

- Morimont F, H.-A. Shanu: photographe, agent de l’Etat et commerçant africain (1858-1905), La mémoire du Congo. Le temps colonial, exhibition catalogue,Tervuren, RMCA, Ghent, Snoeck, 2005, pp. 213-217.

- Pironet L., Architecture thermale : les résidences et villas de Spa, Histoire et Archéologie spadoises. Musée de la Ville d’Eaux Villa Royale Marie-Henriette. SPA. BULLETIN trimestriel, sept. 1981, pp. 110-111.

- Snoep Nanette, Recettes de Dieux, exhibition catalogue, Paris, mqB, pp. 44-45.

- Van der Straeten E., Alexandre J. P. Delcommune; Biographies Coloniales, 1949, col. 257-262.

- Van Schuylenbergh P., Faune sauvage et colonisation. Une histoire de destruction et de protection de la nature congolaise (1885-1960), PIE Peter Lang, Brussels-Berlin, 2020 (Coll. Outre-Mers, vol. 8)

- Vellut J.-L., Les traités de l'Association Internationale du Congo dans Ie Bas-Fleuve Zaïre (1882-1885 ), Un siècle de documentation africaine 1885-1985, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Brussels, 1985, pp. 25-34

- Verswijver G. (éd.), Treasures from the RMCA collection, catalogue exhibition “Hidden Treasures”, Tervuren, RMCA, 2000, pp. 170; 343-344.

- Volper Julien, Art sans pareil, exhibition catalogue, Tervuren, RMCA, p. 15 + exhibition booklet

- Wynants M., Des Ducs de Brabant aux villages Congolais. Tervuren et l’Exposition Coloniale 1897, exhibition catalogue, Un tram pour le Congo, 20/6-16/11/1997, Tervuren, RMCA, 1997, 184 p.

The history of this statue was the subject of research conducted in DR Congo in 2016 by historian Maarten Couttenier. This research provided additional information to that given in the archives available in Belgium. There are certainly more archives and family memoirs both in Belgium and DR Congo that would help expand and enrich this object's biography. Do you have any comments, information or stories to share about this object or type of object? Please contact us: provenance@africamuseum.be.

In the framework of the Taking Care project.