“This is not the Tippu Tip necklace”

29.04.2022

Materials: gilded copper alloy (brass?), glass (paste), silk cord and silver thread, plant fibres

Inventory number: HO.1959.84.1

Recorded in the collections in 1959.

Deposited at and offered for sale to the museum in 1949 by Spiros Dandoudis, a resident of the Belgian Congo.

Believed to have been:

- Received (bought?) by Spiros Dandoudis from a mechanic (perhaps working for Combelga, a Belgian-Congolese trading company) in Kabinda.

- Property of a “mechanic” (anonymous) in Kabinda, 1930s-early 1940s

- Purchased by the latter from Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu (1890-1936), Kabinda, after 1929, or from the colonial administration which had confiscated it (?)

Property of Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu, Kabinda, circa 1919-mid-1930s?

Believed to have been:

- Inherited by Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu from his father Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula (circa 1860-1919), Kabinda

- Property of Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula, Kabinda

- Offered by Hamed ben Mohammed el-Murjebi, also known as Tippu Tip, (circa 1840 - 1905) to Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula, possibly before 1892 (the year of Lumpungu’s submission to the Congo Free State).

A prestigious and uncertain provenance

Listed as “Tippu Tip's necklace” in the AfricaMuseum’s collections of historical objects, the piece’s provenance and the way in which it joined the institution’s collections naturally raise many questions.

Hamed ben Mohammed el-Murjebi (1837 - 1905), commonly known as Tippu Tip, was a major figure in the history of Central and East Africa. He was without doubt the most influential Swahili-Arab trader in the eastern regions of what became the Congo Free State, and in 1887, was even appointed wali (governor) of the State’s trading post in Stanley Falls (now Kisangani).

Possibly born in Zanzibar in the late 1830s, Tippu Tip was the grandson of an emigrant from Muscat (the capital of Oman in the east of the Arabian Peninsula) and the son of an Arab trader, most often based in Tabora (now Tanzania), a pioneer of the inland trade routes. From the age of 18, Tippu Tip travelled in the east of today's DR Congo at the head of one of his father’s trade caravans. With his own caravans, he went on to carry out several journeys further west, enabling him to establish personal control over a vast territory for his ivory trade. However, during the second half of the 19th century, the African territories under Arab control were directly targeted by European imperial expansion under the cover of combating the slave trade. The political and commercial empire that Tippu Tip had built up in Central Africa thus came into conflict with Leopold II’s Congo Free State, the main Western colonial power with which Tippu Tip was forced to negotiate as a competitor, ally and then enemy.

This complex relationship no doubt helped foster his notoriety (as did the propaganda against him) in colonial historiography. This may partly be why Tippu Tip's name was associated with the necklace at the museum, even though the object’s connection with him is distant and based on reported and difficult-to-verify information.

Reverse timeline

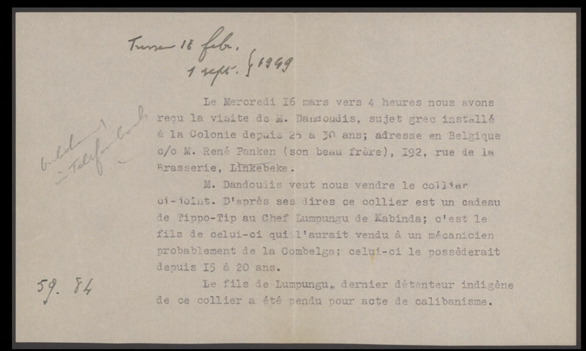

The acquisition records for the necklace only contain a single archive document (shown below). This document contains little verified information, but nevertheless gives an approximate timeline for the object’s journey.

The necklace was recorded in the museum’s historical collections in 1959, even though it had already been at the institution for nearly ten years. In 1949, while on a visit to Belgium, Mr Spiros Dandoudis, a Greek resident of the Belgian colony, offered to sell the necklace and deposited it at the office of the Tervuren museum’s director, F. M. Olbrechts (1899-1958).

The information recorded by the latter states that Spiros Dandoudis received the object from a Belgian mechanic, perhaps working for Combelga (a Belgian-Congolese trading company founded in 1918 in Kabinda to process cotton from the Lusambo region).

This mechanic would have been the owner of the necklace (from the 1930s to the 1940s) in Kabinda, where he himself reportedly bought it (perhaps in the early 1930s) from Chief Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu (1890-1936).

The latter would have inherited the necklace from his father Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula (circa 1860-1919), Chief of Kabinda and its region.

Still according to Dandoudis, Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula received the necklace as a gift from Tippu Tip.

It seems that the museum curator may not have been entirely convinced by the vague information provided by Dandoudis, and/or was unimpressed by the object itself (a relatively mediocre piece of jewellery). Or was it due to the museum’s lack of interest in “Arabised” objects from Central Africa (Couttenier, 2019)? Whatever the reason, the acquisition did not go ahead.

For reasons unknown, however, the object remained at the museum.

It was only ten years later, after the death of Director Olbrechts in 1958, that the necklace was finally recorded in the inventory of the institution’s collections without further clarification of its provenance.

Material aspect of the object: style, materials and supposed origins

Like other Swahili Arab objects associated with Arab traders and fighters (see Rumaliza), the necklace was placed in the institution's historical collections, and not in its ethnographic collections. A differentiation that is certainly scientific (presence or otherwise of written sources), but which tends to artificially reinforce the exogenous nature of the Swahili Arab socio-cultural presence, long marginalised in heritage studies on Central Africa (Arazi & others, 2020). As such, the necklace is unusual and even unique among the museum’s collections (while not going as far as to presume that it is rare).

Compared with three pieces of jewellery currently held at the Musée du quai Branly in Paris, some of the necklace’s features, such as the 10 simple spherical beads and the two droplet end beads, are similar to Yemeni jewellery (Arabian Peninsula), from which Ethiopian jewellers, mainly from the Islamised region of Harar, drew inspiration (Vanderhaegue C., 2001, cat. 228, 229 and 230). These types of beads were used to make fairly short women’s necklaces (with a dozen or so beads), which were generally offered as a wedding gift. On such necklaces, the two end beads are positioned differently, with the spherical part towards the inside.

It is very likely, therefore, that the museum’s necklace was clumsily assembled - by someone who was not a jeweller - in order to include the imposing centre medallion.

Its radiating design with multicoloured glass-paste cabochons around a large central reddish cabochon evokes a more Oriental style, perhaps of Moghul influence (Indian sub-continent). This is a perfectly plausible hypothesis given the old trade links between India and the Sultanate of Oman (South-East Arabia) which from the 17th century controlled areas of the offshore and coastal regions of East Africa. During the first half of the 19th century, its capital was even moved to the island of Zanzibar, where there were several hundred Indian traders. This community grew rapidly and towards 1850 also included craftspeople such as jewellers (S. Laing, 2017, p. 29).

Analysis of the necklace’s materials can take some of these hypotheses further. The spherical and droplet beads are made of gold-leaf copper alloy (probably brass). Because solid gold or silver were not used, it is likely that this was not the work of a Muslim jeweller from the jewellery hubs in Oman, Yemen or Dar es Salam. It may have come from a secondary hub on the East African coast, which were also found in the caravan towns (personal correspondence, C. Vanderhaegue).

As regards the medallion, although it is also made of gilded copper alloy, it could equally have been an import whose place of production and trade are still to be confirmed.

Arab traders, particularly Tippu Tip, of whom photographs and descriptions abound in the literature, did not seem to have worn jewellery themselves. This lack of adornment was common among Muslim men from East Africa. However, many manufactured goods were transported from the coast and exchanged not just as part of trade activities but also to establish alliances. As this necklace was not one of the primary goods (weapons and munitions, fabrics, spices, etc.) used in trade, essentially for ivory and slaves, it could belong to the second category.

A gift from Tippu Tip to Chief Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula?

Tippu Tip held sway over a vast area of Central Africa. Kabinda, to the east of the Kasai region, on the border with Maniema and the former Katanga, was in fact within his sphere of influence. By 1869-1870, Tippu Tip had reached the Lomami region and Songye country, and in the years that followed established personal control over the area to further his ivory and slave business (Merriam, 1974, p. 11).

But Tippu Tip was not the first or only Arab trader to reach this region.

In his autobiography, Tippu Tip only mentions Kabinda once during a short visit (end 1883) at the start of his fourth trip to Central Africa between 1883 and 1886. He nevertheless specifies that at that time the chief of Kabinda, Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula, was already his vassal (Tippo Tip, 157 - Bontinck, 1974, p. 134).

The beginning of their relationship remains difficult to ascertain, and appears non-linear (Renault, 1987, p. 237).

According to some historians, Tippu Tip was called to the Lomami region by Lumpungu’s father Kalamba Kangoi, who requested his assistance (Gillain, 1897, pp. 91-92; Vansina 1966, p. 239). If this is the case, Lumpungu’s first contacts with the Arabs could have been inherited from his father (Merriam, 1974, p. 14). It is not certain, however, that the appeal was exclusively to Tippu Tip in those early days (Dibwe, 2013, p. 46).

It is difficult to ascertain a particular time or circumstance during which Tippu Tip could have potentially offered the necklace to Lumpungu. As the latter was his vassal, Lumpungu himself had to pay tribute to the Arab chief. Moreover, it was generally Tippu Tip’s son, Sefu, who travelled in the region on behalf of his father, and with whom Lumpungu would have had most dealings. They were therefore regularly paid valuable tributes, at least until the end of the 1880s (Huughe, Historique de la chefferie Lumpungu, typescript, 1919, p. 7 - AMAEB AIMO (1577) 8970).

This does not in any way exclude the possibility that in return for such tributes, Tippu Tip, or his son, could have rewarded and encouraged the loyalty of this major regional ally with gifts.

Description of Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula by his great grandson, Jean Mutamba (transcription of an excerpt from an email, 22/08/2021):

“Yes, in our family it was known that, before the Belgians arrived, Chief Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula, as a great warrior of the region, had allied with the Arabs and made an agreement with Tippu Tip to deliver slaves to the Arabs.

There was therefore extensive trade in slaves in exchange for weapons and other manufactured goods and fabrics. It is thanks to these weapons that he was able to impose his power on the other local chiefs.”

In 1892, Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula finally submitted to the Congo Free State. He then assisted the State’s military force, the Force publique, and also directly participated in the campaigns against the “Arabs” (1892-1894), during which many battles took place in Songye country.

During this time, a European trading post was established in Kabinda.

As Lumpungu’s submission to the Congo Free State marked the end of his alliance with the Swahili Arab traders, the necklace would have been offered, if indeed this was the case, before 1892.

Similar objects?

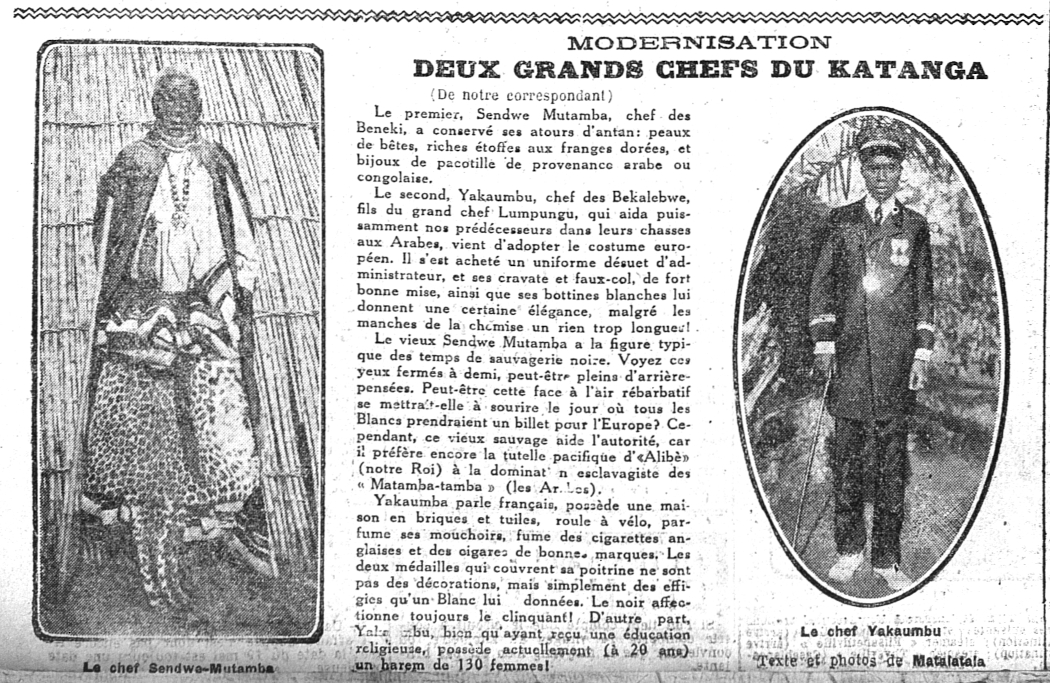

A photograph printed in the Belgian press (La Meuse, 30 April 1924, p. 5 - above) clearly shows chiefs from the region wearing similar jewellery to the museum’s necklace. In the image on the left, Chief Beneki Sendwe-Mutamba is wearing the robes of Songye dignitaries along with a very similar chest piece.

The comment by the journalist who wrote the article, “Modernisation. Deux grands chefs du Katanga”, a correspondent named Matalatala, leaves no doubt as to his opinion of such jewels, which he describes as “trinkets” of Arab origin. It is nevertheless impossible to determine if the piece of jewellery worn by Chief Sendwe-Mutamba in the photo is of exactly the same type, or even the same object, as the one held by the museum.

However, the article's inclusion of the photograph of the young Chief Yakaumbu, son of Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula, for whom Sendwe-Mutamba was minister, does establish a compelling link. Especially as close relations will be maintained between the two men and their families (see below - Popular memories).

Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu

The necklace is therefore linked not only to Tippu Tip, but also Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula, and more particularly his son Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu (1890-1936), who succeeded him in 1919. According to Olbrechts (see document above), he was the “last indigenous owner” of the necklace.

The timeline established using the dates mentioned in the archives shows that the necklace may have been sold by Yakaumbu Kamanda in the early 1930s. A photograph shows that Kamanda, or rather one of his wives (his favourite, Mfute Lushiya - according to the current chief Kamanda) owned the necklace until at least 1929 (image below).

The necklace was at that time worn with beads (now missing) on the upper part of the cord.

“Chief Kamanda [Yakaumbu Lumpungu] had several wives, including Mfute - Lushiye and Musumba Lukombo. It was Mfute that he loved the most, because in all his pictures, in the car, on tour, he was with her.” (Dibwe, 2022, p. 36)

In this photograph, the “decorated” chief appears to be still at the height of his power.

Initial reports from the regional administrators of Lomami District in 1922 described the young chief as highly promising for the regional administration, which was trying to mould him to its liking. As the Lumpungu chiefdom had until then operated autonomously of the colonial regional administration, this step required careful monitoring.

Yakaumbu doit être soutenu et dirigé. Il parait animé de bonne volonté et susceptible de devenir un chef convenable. La punition qu’il a fallu lui infliger au cours de ce trimestre [privation d’un mois de traitement suite à un manquement] ne porte pas atteinte à ce jugement. J’ai exigé que Yakaumbu accompagne l’Administrateur territorial dans ses voyages : il aura ainsi l’occasion de visiter ses populations, de trancher des différends, de s’occuper de sa population et de sa chefferie, bref de faire acte d’autorité.

C’est le seul moyen pratique de lui apprendre son métier et de le débarrasser des éléments peu intéressants dont il a une tendance à s’entourer au village de Kabinda.

“Yakaumbu must be supported and directed. He appears very keen and likely to become an agreeable chief. The punishment that had to be inflicted on him during this quarter [deprivation of one month’s salary following a breach of duty] does not impact this opinion. I have requested that Yakaumbu accompany the Territorial Administrator on his travels: that way he will have the opportunity to visit his people, decide on disputes, take care of his people and his chiefdom, in other words, demonstrate his authority.

This is the only practical way to teach him his job and to rid him of the uninteresting elements that he tends to surround himself with in the village of Kabinda.”

Lomami District - General Administration Report - 2nd Quarter, 1922 - Kabinda Region

Yakaumbu ne manque ni d’intelligence, ni de bonne volonté ; il est jaloux de son autorité, dévoué à l’Etat et en maintes occasions, a montré sa docilité et son désir de coopérer activement à l’administration de sa chefferie. Il nous appartient de tirer parti de ses aptitudes et de ses heureuses dispositions en l’aidant de nos conseils et de nos encouragements.

“Yakaumbu lacks neither intelligence nor willingness; he is very protective of his authority, devoted to the State, and on many occasions has demonstrated his submissiveness and his desire to actively cooperate in the administration of his chiefdom. It is up to us to take advantage of his abilities and his willingness by helping him with our advice and our encouragement.”

Lomami – General Administration Report – 4th Quarter 1922 – Kabinda District

AMAEB, AIMO (1743) 9538

In 1925, while passing through Kabinda on a visit to Congo, Prince Leopold of Belgium gave the young chief a sword of honour.

But Yakaumbu Kamanda’s aura would wane. Both his wealth, some of which was acquired by collecting taxes for the colonists, and the supremacy of his authority stirred dissent among the various populations of his vast territory. In addition, he pursued an autonomous, and even independent, administration like his father.

As the years passed, it became clear that the new chief was not living up to the expectations of the Belgian colonists.

“[...] the political situation in the Kabinda region in general, and in the former Lumpungu chiefdom in particular, was not good. The colonial administration did not manage to make Chief Kamanda ya Kaumbu a submissive and totally devoted purveyor of the colonial cause as it had hoped.” (Dibwe, 2022, p. 43)

As with his father before him, the colonial administrators’ impatience and desire to get rid of an irritating figure of authority prevailed.

On 14 October 1935, following a complaint and witness accounts concerning serious accusations - primarily double homicide and cannibalism - collected during a laborious investigation, which was criticised at the time (anon., L’Affaire Yakaumbu, L’essor du Congo, typed transcription, s. d.), the chief was arrested and imprisoned.

“Relations between Chief Kamanda and the colonial administration were eventually tainted by misunderstandings and deteriorated. The double murder, attributed to Kamanda, of the woman Kapinga wa Tshiyamba and her mixed-race daughter was the colonial administration’s much-awaited opportunity to break ties with the Songye chief.” (Dibwe, 2022, p.49)

The regional administrators, who were careful to avoid problems among the people at the time of the arrest, were delighted.

En ce qui concerne le village de Kabinda et ses environs, ils sont devenus bien plus maniables et l’on n’y sent plus la résistance que nous opposait le Chef sous des dehors polis et zélés.

“As regards the village of Kabinda and the surrounding area, they have become much more pliable, and we no longer sense the resistance that the Chief gave us beneath his polite and zealous exterior.”

Excerpt from the “1935 policy report of the Kabinda region”

AMAEB, AIMO (1599) 9106, a (H-C-4-1 a) Lumpungu

The trial against Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu resulted in his death sentence.

Despite an appeal which questioned the interrogation methods (persuasion, threats and violence) used against the accused (72 in total were cited in the case) and which provoked a judicial counter-inquiry, the appeal for mercy was rejected by the Belgian king. The chief was executed on 1 September 1936.

Ever since, the family and current descendants of Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu have upheld his innocence and have sought to have the memory of their ancestor “officially” vindicated.

What about the necklace?

According to the statements in the museum’s records, Yakaumbu may have sold the necklace shortly before his execution. But it is impossible to know the circumstances surrounding the sale of the necklace, particularly as the name of its buyer, the “mechanic”, remains unknown.

It is however impossible to say whether the chief's previously “princely” existence had declined in the last years of his life (Dibwe, 2022, p. 49).

But in 1932, his imprisonment marked a definitive end to his wealth. His bank accounts were “confiscated” by the colonial administration to cover immediate expenses and costs of the trial:

Il résulte du dossier en possession de l’Administration que les sommes portées au crédit des deux comptes ouverts au nom de votre père ont servi à payer la nourriture spéciale qui lui fut donnée, suite à sa demande, durant son incarcération, les frais de justice et les dommages et intérêts auxquels il fut condamnés.

“The documents before the Administration show that the sums credited to the two accounts opened in your father’s name were used to pay for the special food given to him, at his request, during his imprisonment, the legal fees, and the damages he was ordered to pay.”

L. Henroteaux, Interim Governor of the Province of Kasai to Maole Laurent Lumpungu,

29 February 1960, ref 221.

AMAEB, CAB/B 168 1364

But neither the little information held in the archives, nor the family sources (whose recollections in 1959 focused on the car, the film equipment and the sword offered by Leopold III), make it possible to determine whether the necklace was seized and/or sold in connection with the chief’s imprisonment (correspondence from Laurent Maole Lumpungu with the Ministry of the Belgian Congo and of Ruanda-Urundi - AMAEB, CAB/B, 168, 1364).

The car - shown below - was apparently sold to a close friend of the accused (Mr Jacobs, owner of the Interfina store chain - formerly known as “kasalu” then Comfina - in Kabinda), no doubt to meet his liquidity needs. The real estate was gradually dismantled.

“To erase any trace that could rekindle the memory of Chief Kamanda, the colonial administration confiscated his sword of honour (awarded to him by Prince Leopold in 1925), his car, and his bank account. A portion of the money was used, according to District Commissioner E. Mattelaer, to pay for the legal fees and damages decided in the court ruling. “It is noted,” writes the District Commissioner, “that about 5,000 Frs remained. The file does not mention what this money was used for.” The car was possibly sold to the deceased’s friend, Mr. Jacob, for 15,000 Frs. “It is not known,” continues the District Commissioner, “if this sum was really paid or what it was used for.” The residence of Chief Kamanda, which had remained unoccupied since the death of the Songye Chief, was destroyed by the regional administration during World War II (1940-1945). The roof tiles from the destroyed house were sold to a Belgian colonist by the name of Dumont, while the salvaged bricks were used to build the Kabinda Reine Astrid maternity unit, which became, under Mobutu, the Centre Médical de la Fondation Maman Mobutu. On the ruins of the residence of Chief Kamanda, the colonial authorities later built a modest house for Chief Mutamba, the son and successor of Kamanda. After the country gained independence, Chief Mutamba destroyed this house and, on its ruins, built a princely residence.” (Dibwe, 2022, p. 71)

Popular memories

As much due to the prestige inherited from his father as his tragic end and the highly controversial nature of his death (at the age of 46), Chief Kamanda Yakaumbu Lumpungu has remained a famous figure in Congolese history, including in popular culture (memoirs, stories, songs, paintings) – see the impressive study by Dr. D. Dibwe, 2007 (republished by the museum in 2022).

The museum holds more than a dozen paintings representing Chief Kamanda Yakaumbu and events from his life.

His execution is the theme of the first two.

The oldest (1973) is a work by Tshimbumba Kanda Matulu, a Luba artist (from Kasai) whose father came from Kabinda. Tshimbumba produced several descriptive and realistic paintings of Chief Yakaumbu’s hanging. The museum’s version is the smallest with a portrait-sized frame around the central gallows and three spectators facing him in the foreground (in reality the numbers attending were higher - aside from the crowd which was kept at a distance) – a composition that gives dramatic depth to the scene (in both the actual and figurative sense).

The second version (1989), painted by Kaz, departs from a conventional historical representation and incorporates local collective memory of the event by illustrating a version of his prodigious character. In this painting, it took four hangings to execute the chief who, much to the amazement of the spectators, transformed into different animals the first three times.

“According to popular memory, Kamanda’s power manifested itself in different ways and on several occasions before his hanging.

‘On the day of his execution, Chief Lumpungu was brought to the gallows with his face covered and dressed as a common peasant. According to one legend, Lumpungu, who had many “fetish” power figures, including those that gave him the power to transform into other animate beings, had left his first wife an egg. As long as the egg remained unbroken, death could not claim him. That is how, two or three times, they placed the noose around Kamanda’s neck. But every time the step was pulled away, it was a cockerel or a sheep that was hung, while the accused ended up next to the gallows.’” Dibwe, 2022, p. 64

Later, between 1991 and 1997, Burozi, a painter from Likasi, a former police officer and employee at Lubumbashi zoo, produced a series of works that did not focus on the chief’s execution but rather on his “life story”, illustrating the key elements of his power (family links, impeccable white colonial outfit), his wealth (car) and his trade activities, mostly with the great trader from Elisabethville (now Lubumbashi) Léon Matunga, who is considered the son of Sendwe Mutamba, an ally of Lumpungu Ngoy Mufula. The painter also represents the circumstances surrounding the crime and the chief's arrest. (Michel-N’Tambwe, “Récit de vie recueilli auprès de l’artiste peintre Burozi Jean en date du 12 juillet 1995 Lubumbashi” – Life story from painter Burozi Jean of 12 July 1995, Lubumbashi, unpublished manuscript)

In most of these compositions, the influence of photography is clearly apparent, further highlighted by the predominant use of grey tones.

Two other paintings, in colour this time, feature Kamanda (still painted in grey) with the victims of the double murder of which he was accused. For these two works, excerpts from the record archives gathered by Bogumil Jewsiewicki (RMCA, under inventory), shed more light on the message that the artist wanted to convey.

Regarding the first work, the artist gives a summary of the tragic affair, while asserting the supernatural nature of the victims:

8/ L’histoire de Kamanda Lumpungu, chef Songye avec Kapinga égorgée, sa chaire consommée. Kamanda est furieux. Kapinga, une métisse sans origine, une mystique qui provoqua la pendaison de Kamanda à Kabinda.

“8/ The story of Kamanda Lumpungu, the Songye chief, with Kapinga, her throat cut and her flesh eaten. Kamanda is furious. Kapinga, a mixed-race woman of unknown origin, a mystic who caused the hanging of Kamanda in Kabinda.”

Notes by Michel-N’Tambwe, excerpt from “La description de la peinture” (Description of the painting), n.d.

With the second painting, the artist depicts the situation immediately preceding the murder. In his commentary, he cites jealousy as a possible motive for the criminal act:

10/ Kamanda, Kapinga, sa fille au salon, il s’entretient avec elle pour le mariage. La mystique Kapinga pouvait (sic) son accord, maintenant la femme de Kamanda ayant appris cela, elle devenait jalouse, elle combattit la Kapinga qui trouva la mort. Elle a été dépecée, sa chaire cuite et consommée pour que ce fait reste sans trace. Kamanda voulait avoir une blanche comme femme.

“10/ Kamanda, Kapinga, her daughter in the living room; he talks with her about the marriage. The mystic Kapinga could (sic) her agreement, now Kamanda’s wife found out, she became jealous, she fought Kapinga who was killed. She was cut up, her flesh cooked and eaten to remove all trace. Kamanda wanted a white woman for a wife.”

Notes by Michel-N’Tambwe, excerpt from “La description de la peinture” (Description of the painting), n.d.

The explanation provided by the artist in this instance reflects one of the many oral traditions that place responsibility for the murder on Kamanda’s wives.

As Donatien Dibwe points out (p. 80), “the first wife, Mfute, is the most often cited. As an instigator, she could have encouraged her fellow wives to commit the crime.”

“All these accounts show the wives of Chief Kamanda to be responsible for the death of Kapinga wa Tshiyamba and her daughter. That is why most Songye start this story with the adage: kipama nkiobe kiakushinga nsenga (meaning something like ‘your own wives dishonour you instead of honouring you’). The first wife, Mfute, is the most often cited. As an instigator, she could have encouraged her fellow wives to commit the crime. Moreover, as we will see, this wife was cited as a witness during the trial. The four accounts show that Kamanda died for having wanted to save his wives and preserve his dignity.” Dibwe, 2022, p. 89

Along with two of her fellow wives, Mfute was in fact implicated in the investigation prior to her husband’s trial, but for the charge of concealment (of some of the victim's possessions, which happened to be two pieces of fabric). She was sentenced to one year’s imprisonment and to a fine equivalent to 1/72 of the legal costs.

In addition to the death sentence, Chief Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu was sentenced to pay a fine of 4,000 Belgian francs and 5/72 of the legal costs.

Necklace sold... or seized by the colonial administration?

Was the payment of these costs the reason for the sale - by Mfute or Kamanda - of the necklace or for its seizure by the colonial administration, along with the chief’s other possessions, at the time of his sentence?

The mention of Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu’s death sentence in the museum’s archives (“Lumpungu’s son, the last indigenous owner of this necklace, was hung for acts of cannibalism”) suggests this could be the case.

This is also the opinion of the current Chief Kamanda, the grandson of Yakaumbu Kamanda Lumpungu, who thinks the necklace was confiscated by the Belgian colonists at the same time as his ancestor’s other possessions (video message of 10 October 2021):

While broadly elaborating the historical context of this object, this offers a version of events that this provenance research has been unable to confirm or disprove.

But using current oral sources and the memories they convey adds significant depth to the understanding and interpretation of the partial (and biased) information provided by the written archives.

The works of Professor Dibwe show that for many Congolese, “Chief Kamanda met the criteria of a true man according to Songye tradition” (Dibwe, 2022, p. 89). Many believe that such values associated with his status as chief make the idea that Kamanda would have sold the necklace himself unthinkable.

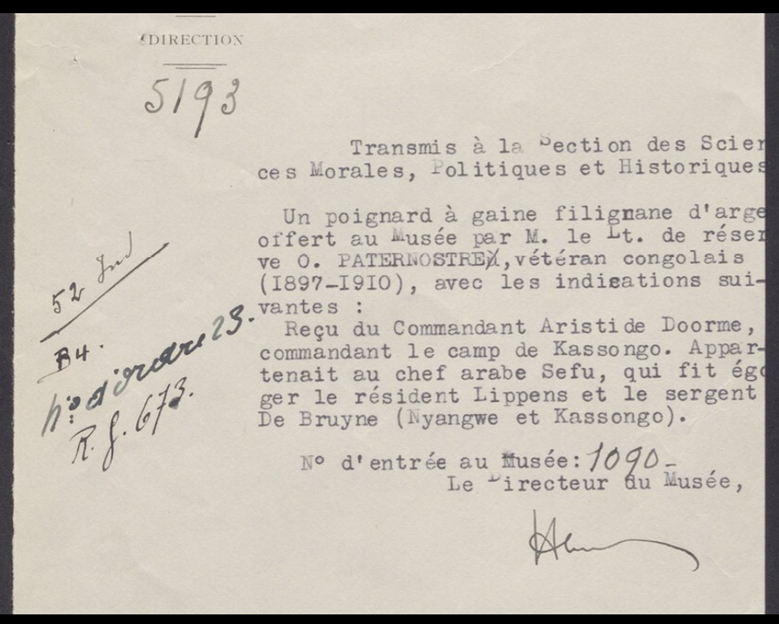

Another object from the same period: Sefu’s Khanjar

Still in the Colonial History Gallery and in the same display as the necklace, is a weapon that belonged to Sefu (circa 1860-1893), Tippu Tip’s son.

This type of knife originates from Oman, where it is called a khanjar and is one of the country’s symbolic objects to this day. The Omani are mostly Ibadi Muslims, a branch of Islam in which men are forbidden from wearing jewellery (except for a signet ring). They are nevertheless allowed to carry weapons, which is why these are so highly worked.

A weapon of prestige, the khanjar is a status symbol for its wearer. It is sometimes offered by families to their sons as they enter manhood and is very often a wedding gift for men. It is also used for practical purposes (M. Vandermeulen).

The khanjar is also used in the rest of the Arabian Peninsula and particularly in Yemen. With the expansion of the Omani Sultanate which, as of the 17th century, comprised the archipelago of Zanzibar and “trading posts” on the East African coast, its use also became widespread among the wealthier African Arab traders of Tanzania and Eastern Congo from the 19th century.

Here again, there is no certainty that the object can be associated with a major figure of the wars of the “Arab campaigns”, circa 1892-1894. The acquisition record does, however, state that before the officer O. Pasternostre gave the dagger to the museum in 1930, it may have been given to him by Commandant Aristide Doorme (1863-1905).

Appointed Lieutenant of the Force publique, Doorme was in fact one of the officers who took possession, in 1893, of one of the boma (fortified villages) that protected Kasongo, Tippu Tip’s and Sefu’s capital.

Doorme attacked the fort of Said ben Abedi, which protected the outskirts of the city and was conquered on the first assault.

The taking of Kasongo by the forces of the Congo Free State seems to have been so swift that many possessions were abandoned and fell into the hands of the Belgians.

But several African Arab chiefs were with Sefu in Kasongo as the city was taken. Sefu escaped and died a few months later in another attack during which Doorme’s role in particular has not been determined. In-depth provenance research concerning this object is being undertaken as part of the CAHN project - Congo-Arab Heritage in Historical Narratives.

Text compiled from a draft by Agnès Lacaille based on specific research and a synthesis of the data below.

SOURCES

Telephone and email exchanges, unpublished sources, etc.:

- Arazi Noemie

- Devos Maud

- Dibwe Donatien

- Genbrugge Siska

- Ghysels Colette

- Hersak Dunja

- Kabuetele Ejiba Dieudonné (via professor Dibwe)

- Leduc Mathilde

- Maniacky Jacky

- Mees Florias

- Morren Tom

- Mutamba Jean (in agreement with family members)

- Nikis Nicolas

- Omasombo Jean

- Sciot Eline

- Van de Voorde Jonas

- Vandermeulen Marleen

- Vanderhaegue Catherine

- Vanderstraete Anne

- Welschen Anne

Archives:

- Archives générales du Royaume (AGR), CC Collection (Conseil colonial et Conseil de législation), record 3392; collection JUST 126 B.

- Archives du Ministère des Affaires étrangères de Belgique (AMAEB): AIMO (1743) 9538; AIMO (1577) 8970; AIMO (1599) 9106; T(270); CAB/B 168 1364

- Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA), Colonial History Section, Acquisition record: DA.7.1558; Private archives: https://archives.africamuseum.be/repositories/2/resources/355

History and Politics Section, Bogumil J Collection.

Press articles (BelgicaPress):

- Meuse (La), 30/04/1924 p. 5; 26, 27 & 28/11/1935 (p.1); 22/4/1936; 3 & 4/10/36 (p. 2); 14/10/36.

Bibliography:

- Arazi, N., Bigohe, S., Luna, O., Mambu, C., Matonda, I., Senga, G., & Smith, A., “History, archaeology and memory of the Swahili-Arab in the Maniema, Democratic Republic of Congo”, Antiquity, 94(375), 2020. E18. doi:10.15184/aqy.2020.86

- Bontinck, F., L'autobiographie De Hamed Ben Mohammed El-Murjebi Tippo Tip (Ca. 1840-1905), Brussels, Académie Royale Des Sciences D'Outre-Mer, 1974, 304 p. (note 411, pp. 267-268)

- Ceuppens Bambi (ed.), Collections du MRAC: Congo art works, peinture populaire, Tervuren, AfricaMuseum, Lannoo, 2016, 187 p.

- Couttenier Maarten, “The Museum as Rift Zone – The Construction and Representation of East and Central Africa in the (Belgian) Congo Museum/Royal Museum for Central Africa”, History in Africa, vol. 46, 2019, pp. 327-358.

- Delcommune Alexandre, Vingt années de vie africaine. Récits de Voyages, d’Aventures et d’Exploration au Congo belge, 1874-1893, Brussels, Vve F. Larcier, 1922, v. 2, pp. 89-99.

- DIBWE dia Mwembu Donatien, “The role of Firearms in the Songye Region (1869-1960)”, in ROSS R., HINFELAAR M. et PESA I. (ed.), The Objects of Life in Central Africa. The History of Consumption and Social Change, 1840-1980, Leiden-Boston, Brill, 2013, pp. 41-64.

- Le Chef Songye Kamanda Ya Kaumbu au rendez-vous de l’histoire et de la mémoire congolaise, Presses universitaires de Lumumbashi, 2005, 172 p. (republished by the RMCA, Tervuren, 2022)

- “Cadres sociaux et politiques de la mémoire : les réincarnations du chef Kamanda ya Kaumbu”, in Likundoli : Mémoire et enquête d’histoire congolaise, X (2006)1-2, p. 110-123.

- Geary Christraud M., In and Out of Focus. Images from Central Africa, 1885-1960, Washington, Smithsonian NMAA, 2002, 128 p.

- Fabian, J. 1996. Remembering the Present: Painting and Popular History in Zaire. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Fisher A., Fastueuse Afrique, Paris, Hazan, 1984, p. 296-7

- Laing S., Tippu Tip. Ivory, Slavery and Discovery in the Scramble for Africa, Surbiton, Medina Publishing, 2017, 330 p.

- Leurquin A., Colliers ethniques d’Afrique, d’Asie … de la collection Ghysels, Milan, Skira, 2003, pp. 111, 172-3

- Merriam Alan P., An African World: the Basongye Village of Lupupa Ngye, Bloomington & London, Indiana University Press, 1974, 347 p.

- Renault François, Tippo Tip. Un potentat arabe en Afrique centrale au XIXe siècle, Paris, Société française d'histoire d'outre-mer, 1987, 376 p. (Bibliothèque d'histoire d'outre-mer. Travaux, 5)

- Sohier Jean, La mémoire d’un policier belgo-congolais, Académie royale des Sciences d’Outre-Mer, Classe des Sciences morales et politiques, N.S., XLII-5, Brussels, 1974

- Vanderhaegue C., Les bijoux d’Ethiopie. Les centres d’orfèvrerie de 1840 à la fin du XXème siècle, thèse de Doctorat, Louvain, UCL, 2001, 3 vol.

- Vellut JL, “Une exécution publique à Elisabethville” in BJ Art pictural zaïrois, 1992, pp. 200-210

Others:

- Blog: Histoire de la Famille Lumpungu

- MuseumTalk: Maarten Couttenier - Het museum als rift zone. De representatie van Oost-Afrika en Arabo-Swahili in het AfricaMuseum (1897-2019)

- Podcast: Mathieu Zana Etambala - Op maat van de overheerser: straf en straffeloosheid in de koloniale rechtspraak

The information in this article is based primarily on resources available at the museum (archives, publications, etc.). The descriptions of these objects and documents can thus always be expanded. Do you have comments, information, or testimonials to share about these or similar objects? Don’t hesitate to contact us: provenance@africamuseum.be.

In the framework of the Taking Care project.