RMCA publications

Équateur Au cœur de la cuvette congolaise.

L'espace socio-culturel mongo dans la province de l'Équateur est très large si l'on englobe la Tshuapa qui fait figure d'arrière-pays, celui des « divers Mongo ». Sur le terrain, certes les groupes mongo sont nombreux mais le « grand peuple mongo » n'est en fait qu'un pur produit de l'anthropologie coloniale. Les missionnaires catholiques du Sacré-Cœur installés à Mbandaka/Bamania firent imposer le lonkundo comme seul parler lomongo unifié. Ils espéraient ainsi prendre le contrepied de la congrégation des scheutistes basée à Lisala chez les Ngombe qui avait assuré la promotion du lingala. En dépit des efforts entrepris, c'est toutefois le lingala qui l'emporta.

Cette situation d'échec au niveau culturel eut son pendant dans la compétition politique au moment de la décolonisation. Initialement sans inclinaison particulière dans ce domaine, les Mongo se jetèrent dans le jeu politique par esprit de revanche face à l'ascendance Ngombe. Ainsi donc, le parti Union Mongo (UNIMO) n'est pas né du dynamisme de l'élite mongo, alors même que l'histoire retient à tort Justin Bomboko comme son fondateur et son président. Lui-même d'ailleurs dit avoir été un « Somi ya Mongo » – Premier des (fils des) Mongo – au sein du parti. Aux élections de 1960, l'UNIMO fut devancée par le Parti de l'Unité nationale (PUNA) de Jean Bolikango, un originaire de la Mongala. Les Ngombe furent de plus en plus perçus comme un obstacle à l'épanouissement mongo et la séparation des deux groupes motiva la création d'une nouvelle entité administrative ethnique mongo dénommée « Cuvette centrale ».

Pendant la Première République (1960-1965), l'élite mongo, divisée et concurrente, domina pourtant la représentation de la province au niveau national. Le président Mobutu, originaire de l'extrême nord de cette « Grande Équateur », connaissait bien la région, les hommes et le milieu mongo de par sa naissance (Lisala) et sa scolarisation (Mbandaka). Sachant que les Mpama, Losakanyi et Banunu-Bobangi ne se sentaient pas proches des Nkundo (Elanga), Ekonda et Ntomba avec lesquels ils furent malgré cela intégrés dans le territoire de Bikoro, il érigea le secteur Lukolela en territoire (1976). Ce fut aussi le cas pour le secteur Mankanza du territoire de Bomongo. Le gain politique prima alors tout autre motif. Les minorités ethniques gagnèrent à la fois en représentation numérique et en terme de postes de pouvoir, attribués aux cercles proches de Mobutu. Accentuant la marginalisation des Mongo, survint la construction plus au nord de la ville de Gbadolite chez les Ngbandi, qui surclassa Mbandaka comme pôle politique provincial.

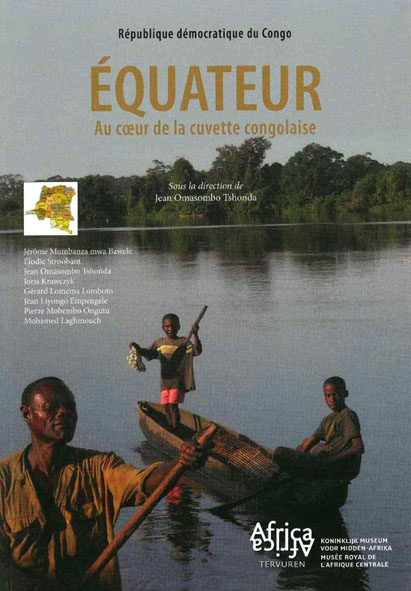

Si elle fut un temps délaissée sur le plan politique, Mbandaka est néanmoins toujours restée un carrefour fluvial dominant vers lequel convergent les embarcations qui font la navette sur le fleuve Congo entre l'Ouest et l'Est de la RDC ; ses nombreux ports l'attestent. C'est aussi à Mbandaka que se rendent les commerçants naviguant sur les différents affluents du fleuve qui drainent l'hinterland. À la descente, le flux concerne les matières premières ; à la montée, ce sont plutôt les produits manufacturés importés pour compenser le déficit de la production locale, sans grande industrie.

En plus d'être le principal moyen de communication, l'eau constitue, au même titre que la forêt, un réservoir alimentaire pour la population ce qui place la province face à un défi complexe. Car les ressources naturelles de l'Équateur, qui semblaient autrefois inépuisables, se révèlent aujourd'hui non seulement limitées mais encore menacées par le mode d'exploitation auquel elles sont exposées. La région demeure cette terre de « cueillette » où règne une anarchie favorisée par l'enclavement géographique. Du caoutchouc au bois wenge, de l'huile de palme au charbon de bois, de l'ivoire au fumbwa ; il est toujours question de produits bruts extraits des forêts et des rivières de la Cuvette congolaise. Celles-ci sont soumises à une pression continue de la part d'une population pauvre et de plus en plus nombreuse.

***

De Evenaarsprovincie, zoals we die vandaag kennen, is niet de provincie waarvan president Mobutu afkomstig is. Het Mongo volk maakt er deel van uit en is in de meerderheid, naast de etnische minderheden op de grondgebieden van Bomongo, Mankanza, Lukolela en andere Ngombe enclaves van de Bolomba en Basankusu territoria. Vergeten we ook niet de Ekonda en de Ntomba, die zelf Mongo zijn maar wiens relaties met de Nkundo-Mongo doordrongen blijven van wantrouwen en zelfs misprijzen en van wederzijdse vooroordelen.

De socioculturele ruimte van de Mongo in de Evenaarsprovincie is zeer ruim, als we hierbij ook Tshuapa betrekken, dat dienstdoet als hinterland, het gebied van de ‘Mongo diversiteit'. Op het terrein zijn de Mongo groepen weliswaar talrijk aanwezig maar het ‘grote Mongo volk' is echter eenvoudigweg een product van de koloniale antropologie. De katholieke Missionarissen van het Heilig Hart, geïnstalleerd in Mbandaka/Bamania, lieten het Lonkundo opleggen als enige spreektaal van het eenvormig gemaakte Lomongo. Op deze manier hoopten zij stokken in de wielen te steken van de congregatie van de scheutisten. Deze laatsten, gevestigd bij de Ngombe in Lisala, hadden alles in het werk gesteld om het Lingala te promoten. Ondanks alle inspanningen was het toch het Lingala dat de overhand kreeg.

Deze mislukking op cultureel vlak vond haar tegenhanger in de politieke wedijver op het moment van de dekolonisatie. Zonder aanvankelijk hierover een specifieke stelling in te nemen, wierpen de Mongo zich op het politieke strijdtoneel, bij wijze van vergelding voor het Ngombe voorgeslacht. Bijgevolg is de partij Union Mongo (UNIMO) niet voortgesproten uit het dynamisme van de Mongo elite, zelfs al gaat Justin Bomboko ten onrechte de geschiedenis in als haar stichter en president. Hijzelf verklaart daarenboven een ‘Somi ya Mongo' – De eerste van (de zonen van) de Mongo – binnen de partij te zijn geweest. Bij de verkiezingen van 1960 werd UNIMO voorbijgestoken door de Parti de l'Unité nationale (PUNA) van Jean Bolikango, afkomstig van Mongala. De Ngombe werden meer en meer gezien als een obstakel voor de ontplooiing van de Mongo en de scheiding van de twee groepen leidde tot de oprichting van een nieuwe administratieve etnische entiteit van de Mongo, genaamd ‘Cuvette centrale' (het centrale Congobekken).

Tijdens de Eerste Republiek (1960-1965) stond de Mongo elite – intern verdeeld en onderling in concurrentie – echter op het voorplan wanneer het ging om de uitstraling van de provincie op nationaal niveau. President Mobutu, afkomstig uit het uiterste noorden van deze ‘Grote Evenaarsprovincie', was door zijn geboorteplaats (Lisala) en zijn opleiding (Mbandaka) heel vertrouwd met de Mongo regio, bevolking en milieu. Hij wist goed dat de Mpama, Losakanyi et Banunu-Bobangi geen affiniteit hadden met de Nkundo (Elanga), Ekonda en Ntomba, met wie ze desondanks opgenomen waren in het Bikoro territorium maar toch verhief hij het district Lukolela tot territorium (1976). Dit was ook het geval voor het district Mankanza uit het territorium Bomongo. De politieke winst kreeg toen voorrang op welk ander motief ook. De etnische minderheden groeiden tegelijkertijd in aantal en in invloedrijke posten, die werden toegekend aan mensen uit de kringen rond Mobutu. Deze marginalisatie van de Mongo werd nog meer in de verf gezet door de oprichting, nog meer in het noorden, van de stad Gbadolite bij de Ngbandi, een stad die Mbandaka voorbijstreefde als politiek centrum van de provincie.

Hoewel Mbandaka een tijdje politiek aan zijn lot werd overgelaten, is de stad altijd een zeer belangrijk kruispunt van rivieren geweest, waar bootjes samenkwamen die heen en weer voeren op de Congostroom, van het westen naar het oosten van de DRC. De talrijke havens in Mbandaka leveren hiervan het bewijs. Het is ook naar Mbandaka dat de handelaars zich begeven vanaf de verschillende bijrivieren vanuit het hinterland. Stroomafwaarts worden vooral grondstoffen aangevoerd; stroomopwaarts ligt de klemtoon eerder op ingevoerde afgewerkte producten, om het tekort van de lokale productie te compenseren, Grootindustrie is daar immers ver te zoeken.

Voor de bevolking is het water, net als het woud, niet enkel het belangrijkste communicatiemiddel, maar ook een voedselreservoir, wat tegelijkertijd de provincie voor een complexe uitdaging stelt. De natuurlijke rijkommen van de Evenaarsprovincie, die altijd onuitputtelijk leken, blijken vandaag immers niet alleen gelimiteerd maar ook nog eens bedreigd door de exploitatiewijze waaraan ze zijn blootgesteld. De regio blijft een ‘verzamelgebied', waar een anarchie heerst die in de hand wordt gewerkt door de geografische insluiting. Of het nu gaat om rubber of wengé hout, palmolie of houtskool, ivoor of fumbwa; steeds zijn het ruwe producten die worden onttrokken aan de wouden en rivieren van het Congobekken. Deze gaan bijgevolg gebukt onder een voortdurende druk vanwege een arme bevolking, die steeds maar in aantal toeneemt.

***

The current province of Équateur is not the birthplace of President Mobutu. It includes the majority Mongo people along with ethnic minorities in the territories of Bomongo, Mankanza, Lukolela and other Ngombe enclaves of the territories of Bolomba and Basankusu. Équateur also includes the Ekonda and Ntomba, who are also Mongo but whose relations with the Nkundo-Mongo are still marked by mutual mistrust, if not outright contempt and prejudice.

The Mongo socio-cultural spaces in Équateur province is vast if we include the Tshuapa who occupy the hinterland, that of the ‘miscellaneous Mongo'. On the ground, there are indeed many Mongo groups, but the ‘great Mongo people' is nothing but a pure product of colonial anthropology. The Catholic Sacred Heart missionaries based in Mbandaka/Bamania imposed Lonkundo as the only unified Lomongo language. In doing so, they hoped to counter the efforts of the Scheutist congregation based in Lisala among the Ngombe, who had worked to promote Lingala. Despite their efforts, Lingala won out.

This failure at the cultural level had its counterpart in the political jockeying that took place during decolonisation. Although they initially had no particular inclinations in this area, the Mongo threw themselves into the political arena out of resentment over rising Ngombe influence. As such, the Union Mongo (UNIMO) party did not arise from the dynamism of the Mongo elite, even though history erroneously credits Justin Bomboko as its founder and president. Bomboko himself states he was a ‘Somi ya Mongo' – First of the (sons of) Mongo – within the party. In the 1960 elections, UNIMO was overtaken by the Parti de l'Unité nationale (PUNA) led by Jean Bolikango, from the Mongala. The Ngombe were increasingly perceived as an obstacle to Mongo success, and the separation of the two groups triggered the creation of a new ethnic Mongo administrative entity called the ‘Cuvette centrale'.

During the First Republic (1960-1965), the divided and competing Mongo elite nonetheless dominated representation of the province at the national level. President Mobutu, a native of the far northern area of this ‘Grande Équateur', knew the Mongo region, people, and milieu well owing to his birthplace (Lisala) and education (Mbandaka). Knowing that the Mpana, Losakanyi and Banunu-Bobangi had little affinity for the Nkundo (Elanga), Ekonda, and Ntomba with whom they were nonetheless integrated in the territory of Bikoro, he established the Lukolela district as a territory (1976). This was also the case for the Mankanza district in Bomongo territory. The political gain prevailed over all other motives. The ethnic minorities had more representatives and positions of power, awarded to those close to Mobutu's circles. The construction further up north of the city of Gbadolite among the Ngbandi exacerbated the marginalisation of the Mongo, as it supplanted Mbandaka as the province's political centre.

While Mbandaka was neglected for a time on the political level, it still remained a dominant river town towards which boats converged as they travelled between the country's east and west, as evidenced by its many ports. Traders sailing on the river tributaries draining the hinterland also flocked to Mbandaka, bringing raw materials to the town and departing with imported manufactured goods to compensate for the lack of local production and the absence of major industries.

In addition to being the main channel of communication, the water – like the forest – represents a food reservoir for the population, which pits the province against a complex challenge. The once seemingly limitless natural resources of Équateur have now been revealed to be not only finite, but threatened by the manner in which they are being used. The region remains an area of ‘harvest' where the reign of anarchy is encouraged by geographic isolation. Rubber, Wenge wood, palm oil, charcoal, ivory, fumbwa: all are raw materials sourced from the Congolese cuvette's forests and rivers, which are under constant pressure from a poor and growing population.

Freely available at this link

Freely available at this link