RMCA publications

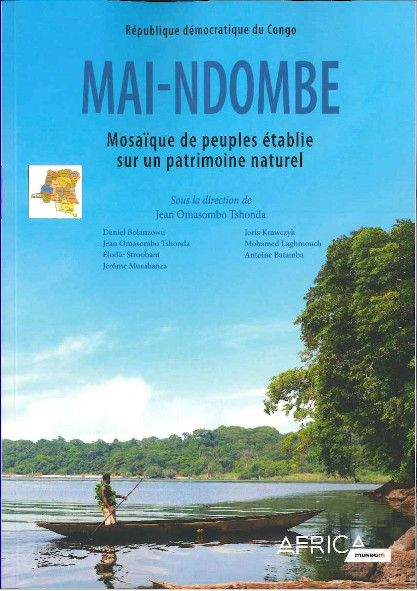

Mai-Ndombe. Mosaïque de peuples établie sur un patrimoine naturel

Historiquement, le vaste espace du district primitif devenu aujourd'hui province correspond à la réserve personnelle au nord de la rivière Kasaï que s'était taillée Léopold II dans l'État indépendant du Congo, connu sous le nom de « Domaine de la Couronne », et dont les limites comme l'identité de ses administrateurs et commissionnaires restent nébuleuses. La région, riche en caoutchouc, fut saignée à blanc par le système de prédation économique organisé par Léopold II, qui écrasa les formes antérieures d'échanges lui faisant concurrence et abandonna certains territoires et ses habitants à l'extraction brutale par les agents européens et leurs auxiliaires.

Le Mai-Ndombe est une mosaïque à la fois géographique et humaine. D'une part, on ne trouve pas dans la configuration naturelle d'élément fédérateur. La position centrale du lac n'en fait pas un ferment d'unité. Elle sert davantage de repère géographique symbolique qu'elle n'est un berceau d'identité. Le lac rallie sur ses rives les territoires de Kutu, Inongo et Kiri qui forment le noyau historique de la province. Les territoires de Yumbi, Bolobo, longtemps acquis à l'Équateur, Mushie et Kwamouth au Congo-Kasaï, et Oshwe, à Dekese, y ont été additionnés tardivement. L'hétérogénéité se retrouve partout. La forêt, qui est faite reine dans le nord et l'est de la province, cède le pas à la savane au sud et à l'ouest. D'autre part, un déséquilibre démographique se calque sur le clivage végétal : on constate un vide au niveau du territoire forestier d'Oshwe très peu peuplé, intégré à la Cuvette centrale. Les territoires voisins de Kiri et d'Inongo, un peu plus habités, voient leur population disséminée le long du lac, des rivières et de quelques routes. Ce désert vert au nord et à l'est contraste avec des poches de peuplements très concentrées à l'ouest et au sud (ou une partie du sud) dont les densités moyennes sont beaucoup plus élevées. Un dénominateur commun aux organisations qui régissent les peuplements du Mai-Ndombe est donc difficile à trouver.

Le gros fil des coutures administratives assemble donc des sous-espaces aux spécificités socioculturelles, politiques et économiques bien distinctes. L'histoire de la construction de cette entité provinciale ne serait-elle donc que le fruit d'un empiècement administratif opéré par l'État moderne ? Celui-là même qui dès le départ a négligé les questions humaines face aux impératifs économiques.

Le Mai-Ndombe, c'est aussi un patrimoine naturel forestier qui recouvre les trois quarts de la province. Ressource vitale autant que source d'autorité et de prestige, elles renferment une biodiversité exceptionnelle qui a justifié la création d'un certain nombre d'espaces de conservation. La province capte d'importants financements, gage de leur préservation. Mais pour le moment, la richesse de ce patrimoine naturel reconnu au niveau mondial contraste avec la précarité socio-économique de ses habitants dont les pratiques agricoles intensives sont montrées du doigt comme les principales causes de déforestation. À côté des activités de pêche, plus ou moins importantes selon les groupes et leur proximité avec le fleuve, le lac ou une rivière, et de chasse selon la disponibilité du gibier, la majorité des habitants exerce une activité commerciale en complément. Chargés systématiquement à la démesure, les baleinières rudimentaires et quelques rares bateaux traversent le lac et descendent les rivières et le fleuve vers la capitale. En l'absence de toute industrie, ces mêmes unités transportent à la montée les produits manufacturés consommés localement. Les caractéristiques de ces flux d'échanges renvoient curieusement au régime de cueillette de l'époque léopoldienne. À l'instar du caoutchouc, du copal ou de l'ivoire d'hier, les produits marchands d'aujourd'hui, à l'exception du bois de la Sodefor, sortent à l'état brut vers Kinshasa.

***

Door zijn oprichting in de moderne Staat in 1895, werd Mai-Ndombe, het ‘district van het Leopold II meer', ontologisch gedetermineerd door het koloniaal kapitalisme en tot twee keer toe geassocieerd met een van de meest notoire en controversiële figuren uit deze periode. Vandaag heeft de topologische schoonmaakoperatie, uitgevoerd door de ‘authenticiteit' van het Mobutu-regime, alle verwijzingen naar de vroegere Belgische vorst gewist. Op dezelfde manier werd ook geprobeerd de provincie los te koppelen van zijn meer door zijn naam uit deze laatste benaming weg te laten. Maar de provincie heeft zich toch nog niet ontdaan van zijn koloniale stempel. De term ‘Mai-Ndombe', letterlijk ‘zwarte wateren', die de staat Zaïre gebruikt ter vervanging van het vorige ‘Leopold II meer', houdt in feite een fysisch kwalificatief in dat de Bakongo-begeleiders van H.M. Stanley aan het meer gaven toen ze er langskwamen.

Historisch gezien, komt de uitgestrekte ruimte van het oorspronkelijke district dat nu provincie is geworden overeen met het persoonlijk domein dat Leopold II zich ten noorden van de Kasaï-rivier heeft toegeëigend in de Onafhankelijke Congostaat. Het gebied staat bekend onder de naam ‘Kroondomein' en er bestaat nog veel onzekerheid over zowel zijn grenzen als de identiteit van zijn beheerders en commissionairs. De streek, rijk aan rubber, onderging een ware aderlating, door het systeem van economische predatie dat Leopold II opzette. Hij drukte alle vroegere handelsvormen die ermee concurreerden resoluut de kop in en liet bepaalde gebieden en de inwoners ervan in de handen van de Europese beheerders en hun personeel, die er op een brutale manier het rubber gingen winnen.

Mai-Ndombe is een geografisch én menselijk mozaïek. Langs de ene kant is er geen eenheid op het vlak van de natuurlijke opbouw. De centrale ligging van het meer draagt niet bij tot zijn eendracht; in plaats van aan de provincie een zekere identiteit te verlenen, doet het meer dienst als een symbolisch geografisch oriëntatiepunt. Langs dit meer vinden we de territoria van Kuto, Inongo en Kiri, die de historische kern van de provincie vormen. Later werden hieraan de volgende gebieden toegevoegd: Yumbi, Bolobo, lange tijd voordien verworven van Equateur, Mushie en Kwamouth van Congo-Kasaï en Oshwe van Dekese. De grote verscheidenheid is overal terug te vinden. Het woud, dat overheerst in het noorden en het oosten van de provincie, gaat over in savanne in het zuiden en het westen. Daarnaast weerspiegelt een demografisch onevenwicht de tegenstellingen in vegetatie: er is een grote leegte in het zeer dun bevolkte woudgebied van Oshwe, dat deel uitmaakt van het centrale Congobekken. In de naburige territoria van Kiri en Inongo, die iets meer bewoond zijn, is de bevolking verspreid langs het meer, de rivieren en enkele wegen. Deze groene woestijn in het noorden en oosten staat in schril contrast tot gronden met een heel geconcentreerde bevolking in het westen en het zuiden (of een deel van het zuiden), waar de gemiddelde bevolkingsdichtheden veel hoger oplopen. Het is bijgevolg moeilijk een gemeenschappelijke noemer te vinden voor alle manieren waarop de bevolkingsgroepen van Mai-Ndombe worden georganiseerd.

Het grote administratieve netwerk brengt zo kleinere regio's samen met duidelijk verschillende socioculturele, politieke en economische kenmerken. Was de geschiedenis van de opbouw van deze provinciale eenheid dan enkel het resultaat van een administratief patchwork dat de moderne Staat heeft gecreëerd, dezelfde staat die van bij het begin geen oog had voor de menselijke problemen ontstaan door de economische imperatieven?

Mai-Ndombe, dat is ook een natuurlijk erfgoed. Drie vierden van de provincie is bedekt met bos, een bron van leven, autoriteit en prestige met een uitzonderlijke biodiversiteit die met recht en reden leidde tot de creatie van een bepaald aantal conserveringszones. De provincie wordt in hoge mate gefinancierd om deze te behouden. Maar op dit moment is er een schril contrast tussen dit wereldnatuurerfgoed en de socio-economische instabiliteit van zijn inwoners, wiens intensieve landbouwpraktijken met de vinger worden gewezen als de belangrijkste oorzaken van de ontbossing. Naast visvangst, waarvan het belang afhangt van de verschillende bevolkingsgroepen en hun nabijheid tot de stroom, meer of een rivier, en de jacht, afhankelijk van de beschikbaarheid van wild, oefenen de meeste inwoners nog een bijkomende commerciële taak uit. Rudimentaire walvisvaarders en enkele zeldzame boten, alle systematisch overladen, steken het meer over en dalen langs de rivieren en de stroom af naar de hoofdstad. Bij gebrek aan enige vorm van industrie, transporteren deze vaartuigen bij hun terugkeer ook afgewerkte producten die dan lokaal worden verbruikt. Deze handelsstromen vertonen een merkwaardige gelijkenis met het oogststelsel uit de tijd van Leopold. Net als bij het rubber, de kopal of het ivoor van vroeger worden de handelsgoederen van vandaag, uitgezonderd het hout van Sodefor, in onbewerkte toestand naar Kinshasa vervoerd.

***

With its advent into the modern State in 1895, Mai-Ndombe – called ‘Lake Leopold II district' – became ontologically determined by colonial capitalism and associated twice over with one of its most prominent and controversial figures. Today, the topological sweep carried out by the ‘authenticity' of the Mobutu regime has removed all references to the former ruler of Belgium. Likewise, an attempt was made to dissociate the province from its lake by erasing its name from the latter. But the province still bears traces of its colonial markers. The term ‘Mai-Ndombe', meaning ‘black waters', that the State of Zaïre used to replace the old ‘Lake Leopold II', effectively designates a physical qualifier that was given to the lake by H.M. Stanley's Bakongo carriers when he passed through in 1882.

Historically, the vast primeval district area that is now a province corresponds to the personal reserve known as the ‘Crown Domain' carved out by Leopold II north of the Kasai River in the Congo Free State, and whose limits, like the identities of its administrators and commissioners, remain unclear. The rubber-rich region was bled white by the system of economic predation organized by Leopold II, which suppressed all other forms of trade that competed with it and abandoned certain territories and their inhabitants to brutal treatment by European agents and their auxiliaries.

Mai-Ndombe is both a geographic and human mosaic. No unifying element can be found in its natural configuration. The lake's central position does not make it a catalyst for unity. It serves more as a symbolic geographic marker rather than a cradle of identity. The territories of Kutu, Inongo, and Kiri, which form the province's historical nucleus, are found on the shores of the lake. The territories of Yumbi, Bolobo, long acquired from Équateur; Mushie and Kwamouth from Congo-Kasaï; and Oshwe, from Dekese, were added much later. Heterogeneity is everywhere. The forest, which reigns supreme in the north and east of the province, gives way to savannah in the south and west. Moreover, a demographic imbalance matches the disparity in vegetation: there is an emptiness in the very sparsely populated forest territory of Oshwe, part of the Congo basin. The neighbouring territories of Kri and Inongo, with somewhat denser populations, see their inhabitants scattered along the lake, rivers, and a few roads. This green desert in the north and east stands in stark contrast to the highly populated pockets of land found in the west and south (or part of it), whose population densities are much higher. A common denominator for the manner in which Mai-Ndombe populations are organized is thus hard to find.

The thick administrative thread thus stitches together smaller areas with very distinct socio-cultural, political, and economic characteristics. Was the construction of this provincial body simply a piece of administrative patchwork created by the modern State, the same one that – from the outset – prioritised economic needs and neglected social considerations?

Mai-Ndombe is also synonymous with natural heritage. Three-quarters of the province is covered by forest, a source of authority and prestige as well as a vital resource, containing exceptional biodiversity that has warranted the creation of a number of conservation areas. The province receives significant funding to preserve them. But for now, the wealth of this globally recognized natural heritage stands sharply at odds with the precarious socio-economic situation of its inhabitants, whose intensive farming practices are often singled out as being a leading cause of deforestation. Along with fishing (of varying intensity depending on the group and on proximity to the rivers or lake) and hunting, depending on the availability of game, most inhabitants also engage in a supplementary trading activity. Rudimentary whalers and a smattering of boats, all systematically overloaded, cross the lake and go down the rivers towards the capital. In the absence of industry, these same vessels head back in the opposite direction bearing manufactured goods that are consumed locally. The characteristics of these trade flows bear a curious resemblance to the harvesting regime of Leopold's time. Like the rubber, copal and ivory of yesteryear, today's commodities – with the exception of Sodefor timber – leave for Kinshasa as raw materials.

Freely available at this link

Freely available at this link