The Kongo kingdom

The Kongo kingdom is one of Africa’s ancient kingdoms whose history is exceptionally well documented. This article highlights some pieces of this rich, centuries-old history, and deconstructs some of the stereotypes that still persist today about the history of Africa.

Mbanza Kongo (São Salvador). Engraving. From O[Ifert] Dapper, Naukeurige beschrijvinge der Afrikaensche gewesten, 1668, p. 562-63.

The Kongo kingdom: a long history

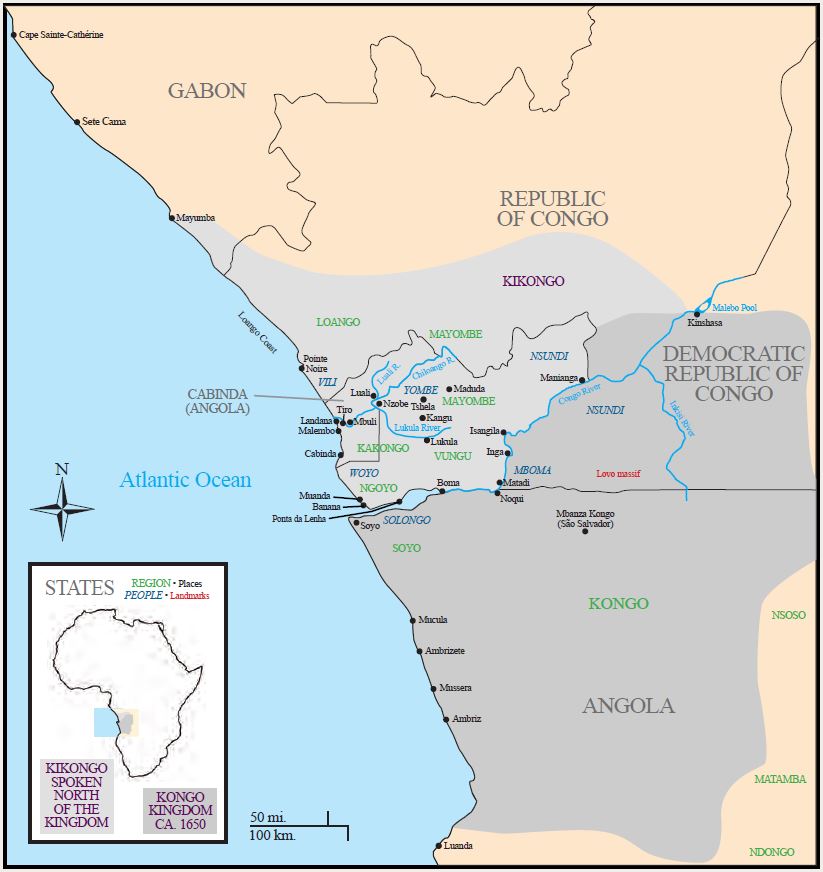

At its height, the Kongo kingdom covered parts of present-day Angola, DR Congo and Republic of Congo.

According to oral traditions, Nimi a Nzima of Mpemba Kasi and Nsaku Lau of Mbata founded the kingdom at the end of the 14th century. They agreed that the descendants of Nimi a Nzima would be its kings, while those of Nsaku Lau would rule Mbata.

Subsequently, Lukeni lua Nimi (c. 1380-1420), son of Nimi a Nzima, became the first Kongo king. He declared Mbanza Kongo (located in present-day Angola) capital of the kingdom.

When Portuguese sailors arrived off the coast of the Kongo kingdom in 1483 in search of political and commercial alliances, the kingdom was already a powerful and centralised state, which made a strong impression on its visitors. In 1491, the Milanese ambassador in Lisbon compared the capital Mbanza Kongo to the prestigious city of Évora, the royal residence in Portugal.

Map of the Kongo kingdom ca. 1650. At its height, the Kongo kingdom covered parts of present-day Angola, DR Congo and Republic of Congo. Sometimes Kongo is said to have occupied even a part of present-day Gabon. This mistaken assertion is based on the assumption that the extent of the Kongo kingdom coincided with the geographical area in which variants of the Kikongo language are spoken today. Recent research has shown, however, that the dispersion of Kikongo predates the origin of the Kongo kingdom (Bostoen & de Schryver 2018) and that the influence of Kongo in the coastal areas north of the Congo River was mostly symbolic (Thornton 2020).

Map borrowed from the book:

Cooksey, Susan, Robin Poynor, Hein Vanhee, and Carlee S Forbes, eds. 2013. Kongo across the Waters. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. Page 16.

A quick embracement of Catholicism

In 1491, less than ten years after the first contacts with the Portuguese, King Nzinga a Nkuwu (1483-1509) converted to Catholicism. He then took the name of the Portuguese king, João I. Young Kongolese educated in Europe wrote the letters that the king sent to Portugal.

His son, King Afonso I, helped to develop and spread the Christian religion within his kingdom. He sent students to Europe and studied the Christian religion himself.

An interest in European culture, but a preservation of autonomy

Afonso I also tried to establish direct relations with the Vatican. In 1513, he sent his son Henrique to the Vatican to become a bishop. Afonso I's intention was to make the Kongo church independent and self-sufficient, like that of Portugal. In 1518, Henrique became bishop, with the status ‘in partibus infidelium’ (‘in infidel areas’). When he returned to the Kongo kingdom, his bishop’s status enabled him to appoint the Kongolese priests himself in order to spread Christianity within the kingdom. Henrique died in 1531. In 1534, the papacy turned the Kongo church into a branch of the Diocese located on the Portuguese island of São Tomé, giving the Portuguese greater political influence.

Although Afonso I showed an interest in what Portugal could offer him, for example literacy, he strongly resisted Portuguese attempts to settle deep within his territory. He reserved the right to restrict access to his kingdom. Around 1515, he opposed Portugal's trade connections with the neighbouring kingdom of Ndongo. He also refused to cede control of the slave trade. In the early 1510s, several thousands of slaves were sold every year, mostly to work on the sugar plantations in São Tomé.

African Ambassadors in Europe

Photo from the book :

Cooksey, Susan, Robin Poynor, Hein Vanhee, and Carlee S Forbes, eds. 2013. Kongo across the Waters. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. Page 53.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the Portuguese became more and more aggressive. The Kongo kingdom intensified its efforts in European diplomacy.

For about ten years, Kongo king Alvaro II sent letters denouncing the hostile attitude of the Portuguese governors of Angola. Then, in 1604, he sent Antonio Manuel to Rome as his ambassador. His mission dealt both with the problems related to his now hostile Portuguese neighbour, Angola, and with the difficulties encountered with a bishop appointed by the Portuguese, who hoped to use religion to extend Portuguese influence.

Antonio Manuel first went to Brazil, where he freed a Kongo nobleman who had been made a slave. On his journey from Brazil to Europe, his ship was attacked by Dutch pirates. He managed to escape, but arrived in Lisbon ruined. Nonetheless, he impressed his European hosts, who saw in him an urbane and educated man of great faith. Antonio Manuel spent four years seeking the support of rich sponsors to complete his mission. He finally succeeded and arrived in Rome in 1608. But his sudden death shortly afterwards prevented him from engaging in negotiations. He received the last sacraments from Pope Paul V and was buried with great pomp. A portrait bust of Manuel is kept in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome.

In the following years, the Portuguese governors of Angola carried out attacks and pillaged the neighbouring kingdom of Ndongo. In 1622, the Portuguese governor decided to attack the Kongo kingdom. The Kongo elite and its new king Pedro II managed to defeat the assailants in 1623. Kongo diplomacy then moved up a gear. Pedro II sent letters to the Pope and the King of Spain, declaring that the Portuguese governor had no right to invade his kingdom, a Christian land. He therefore demanded the return of prisoners. The pope agreed and more than 1000 prisoners returned from Brazil to Kongo.

The Kongo kingdom also formed an alliance with the Netherlands through the Dutch West India Company. The latter agreed to attack Angola as part of a joint offensive in 1624, but the death of Pedro II that year and the Portuguese conciliation led Pedro II's son and successor, Garcia I, to renounce attacking Angola. Nevertheless, relations between the Netherlands and Kongo were maintained. When the Portuguese armies continued to put pressure on Kongo, King Garcia I renewed the alliance with the Dutch West India Company. This time the joint invasion took place. A Dutch fleet seized Luanda in 1641, and the Kongo armies cooperated with the Dutch forces to drive the Portuguese out of their positions near the city, forcing them to withdraw to their fort at Massangano, more than 100 km from Luanda.

Kongo chiefs lose their sovereignty

In Central Africa, the Atlantic slave trade – which began in the 16th century – ended in 1866. In the 1870s, African communities on the Atlantic coast and along the banks of the Chiloango and Congo rivers responded en masse to the demand for raw materials from the industrialising Western countries by turning to the production of palm oil, ivory, rubber, peanuts and coffee.

The Kongo chiefs and their allied political factions occupied strategic positions along navigable rivers and major overland trade routes. In order to protect their trade, they carefully controlled the movements of European merchants inland. For example, in the 1850s, the Liverpool company Hatton & Cookson had an agreement that allowed them to sail up the Chiloango River, but not beyond the village of Tiro, 8 km from the coast. Barrages and guards with poisoned arrows ensured compliance with this restriction. In the early 1870s, Germans noted the presence of several toll posts in the interior of Mayombe. Commercial caravans were inspected and taxed there.

Until the 1880s, European traders thus bought their goods mainly along the coast and at the mouth of the Congo River, under conditions that were largely determined by Africans.

The 1880s marked the beginning of a new era. Kongo chiefs were often duped into signing treaties by which they ceded sovereignty to European states in return for a small tribute. After the Berlin conference of 1885, the interior lands of Africa were conquered and occupied manu militari, which was accompanied by extreme violence and resistance. The aim of the European powers was to gain direct control over natural resources, labour and production. In the Congo Free State of Leopold II, all non-cultivated land (‘terres vacantes’) was appropriated and then ceded in concessions to colonial companies. In order to exploit ivory and rubber in particular, these companies imposed forced labour on the population, often under inhumane conditions.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the consolidation of the colonial regime led to the impoverishment of Kongo chiefs and traders throughout the Bas-Congo region.

These few elements of the long history of the Kongo kingdom make it possible to deconstruct some stereotypes about the history of the African continent and colonisation:

- Before Belgian colonisation, Africans did not live as ‘tribes’, independently of each other. There were powerful political and economic structures in Africa.

- When Leopold II sent soldiers to the Congo, the states they encountered in the coastal regions already had a long history in common with Europe. The links between Africa and Europe go back several centuries before Belgian colonisation.

- Like the Europeans, the people of Central Africa moved around, often over great distances, and maintained major trade routes. The Belgian 'pioneers' did not travel through 'jungles' during their 'explorations'. They used these centuries-old trade routes.

- Land and resources were already being exploited long before the arrival of the Europeans.

Dom Miguel de Castro was ambassador of the Kongo kingdom in the Netherlands in the 1640's.

Painting by Jasper Beckx (active ca. 1627-47). Oil on canvas, 75 x 62 cm. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

This article is based on the following publications:

- Thornton, John K. 2015. ‘The Kingdom of Kongo’. In Kongo: Power and Majesty, edited by Alisa LaGamma, 97–117. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Heywood, Linda, and John Thornton. 2013. ‘The Kongo Kingdom and European Diplomacy’. In Kongo across the Waters, edited by Susan Cooksey, Robin Poynor, Hein Vanhee, and Carlee S Forbes, 52–55. Gainesville FL: University Press of Florida.

- Vanhee, Hein. & Vos, J. 2013. ‘Kongo in the Age of Empire’. In: Susan Cooksey, Robin Poynor, Hein Vanhee & Carlee S. Forbes (eds), Kongo across the Waters. Gainesville, FL : University Press of Florida, pp. 78-87.

Read more:

- Thornton, John K. 2020. A History of West Central Africa to 1850. Cambridge, United Kingdom ; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Bostoen, Koen, and Inge Brinkman, eds. 2018. The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Clist, Bernard, Pierre de Maret, and Koen Bostoen, eds. 2018. Une archéologie des provinces septentrionales du royaume Kongo. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Bostoen, Koen, and Gilles-Maurice de Schryver. 2018. « Langues et évolution linguistique dans le royaume et l’aire kongo ». In Une archéologie des provinces septentrionales du royaume Kongo, ed. Bernard Clist, Pierre de Maret, and Koen Bostoen, 51. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Vos, Jelmer. 2015. Kongo in the Age of Empire, 1860-1913: The Breakdown of a Moral Order. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press.

- Heimlich, Geoffroy. 2017. Le massif de Lovo, sur les traces du royaume de Kongo. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Fromont, Cécile. 2014. The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Cooksey, Susan, Robin Poynor, Hein Vanhee, and Carlee S Forbes, eds. 2013. Kongo across the Waters. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Volper, J., N'sondé, S-R., Thornton, J. K., & al., 2016, Du Jourdain au Congo : art et Christianisme en Afrique centrale, éditions Flammarion, Paris.