KMMA publicaties

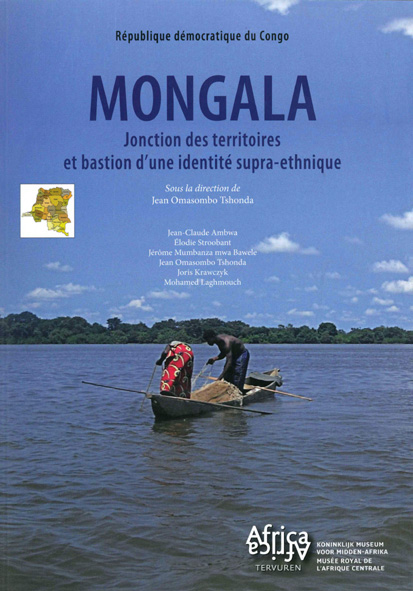

République démocartique du Congo. Mongala. Jonction des territoires et bastion d'une identité supra-ethnique.

Son agencement renvoie avant tout à des considérations politico-administratives. La Mongala en a hérité son étirement d'ouest en est, qui traduit l'ambition de regrouper un noyau de peuplement ngombe autour de Lisala et de rattacher les Budja installés en territoire de Bumba, traditionnellement apparentés aux populations de la Province-Orientale (Mbole/Mobango, etc.). C'est en 1955, lors de la dernière grande réforme administrative du Congo belge, que Bongandanga fut ajouté comme appendice. Cette évolution tourmentée est l'expression même d'un ensemble disparate, qui paraît être l'effet d'une position géographique de transition dans la confluence entre les espaces des peuplements mongo, « Gens d'eau », ngbaka, ngbandi, etc. et qui passe pour être un assemblage à la fois des peuples et des territoires marqués par leur éparpillement.

L'édification de la Mongala pose, en creux, le problème de l'identité, car la singularité régionale du district s'est forgée dans un double rapport concurrentiel : celui, extérieur, opposant les « autochtones » aux ethnies voisines, en particulier les Ngombe aux Mongo ; et celui, intérieur, mettant en présence deux populations dominantes, les Ngombe et les Budja. Si les tensions entre Ngombe et Mongo émergèrent à l'indépendance autour du leadership politique dans la province de l'Équateur, elles trouvent leur origine dans les rivalités entre les pères scheutistes et les missionnaires du Sacré-Cœur. Les divers peuples de la Mongala font partie, au sens large, du groupe des Bangala, une identité supra-ethnique fondée sur la langue commerciale des populations riveraines du fleuve Congo. Codifiée et diffusée à travers l'enseignement, cette langue se répandit aussi via la Force publique.

Vu de l'extérieur, elle modela l'identité de la Mongala, une identité qui s'imposa, en retour, dans l'ensemble de la province de l'Équateur. L'identité mongo s'inscrit en contrepoids de ce succès, en s'appuyant sur la promotion de la langue lomongo, qui devait prendre le contrepied du lingala.

En interne, les particularismes s'affirment et s'ancrent jusque dans l'organisation de l'espace. Ngombe et Budja passent pour être des rivaux et leur antagonisme s'exprime symboliquement dans l'opposition entre leurs chefs-lieux administratifs respectifs. Lisala-la-bureaucratique, siège et foyer d'instruction au rayonnement culturel, tutoie Bumba-la-marchande et ses plantations environnantes, point focal du peuplement et des activités économiques dans le Nord du pays.

Espace dominé par la forêt et ponctuellement consacré aux cultures agricoles, ses richesses naturelles ont attiré de tout temps les convoitises : elles valent à la région d'être le lieu de méthodes d'exploitation qui ont nourri, et nourrissent encore, la controverse. Les activités humaines y réunissent les caractères d'une économie extravertie dont la Mongala fit d'ailleurs les frais (humains et environnementaux) dès la fin du XIXe siècle. Les stigmates du « caoutchouc rouge » y sont longtemps restés vivaces et les campagnes récentes contre les spoliations forestières semblent leur faire écho, charriant, en outre, la délicate thématique de la protection de l'environnement (forestier). Du passé au présent encore, le fleuve et ses ramifications constituent l'un des éléments majeurs de continuité, sinon le principal, dans les évolutions économiques locales.

Assurant la jonction de plusieurs territoires, le réseau hydrographique de la Mongala relie celle-ci au district de l'Équateur et à Kinshasa, au Sud- et au Nord-Ubangi, à l'Ituri et aux deux Uele, à partir d'Aketi et, enfin, à Kisangani. Bumba et Lisala drainent les surplus agricoles et les produits forestiers de leur arrière-pays pour les réexpédier par le fleuve vers les régions voisines, ou par la route vers la République centrafricaine (via Akula-Zongo). Portée avant tout par ces voies naturelles, la Mongala représente un bassin de production important, à la santé en phase de rémission. Ce qui, combiné à une situation géostratégique privilégiée, lui vaut d'être la cible de plusieurs programmes de développement gouvernementaux et privés.

***

Zelfs met een oppervlakte van 58 141 km2 vormt Mongala, met slechts drie territoria, het kleinste administratieve geheel van de 26 provincies van de DRC voorzien in de Grondwet van 18 februari 2006.

Haar indeling is in de eerste plaats een weerspiegeling van politiek-administratieve motieven. Deze hebben ertoe geleid dat Mongala uitgestrekt is van west naar oost : het toont de wil om een kern van Ngombe volkeren bijeen te brengen rond Lisala, en de Budja, die gevestigd zijn in het Bumba territorium, eraan toe te voegen. Deze laatsten zijn traditioneel verwant aan de bevolkingsgroepen van de Province-Orientale (Mbole/Mobango, enz.). Het is in 1955, tijdens de laatste grote administratieve hervorming van Belgisch Congo, dat Bongandanga werd ingelijfd. Deze veelbewogen evolutie is op zich de weergave van een discordant geheel, het ogenschijnlijke gevolg van een geografische overgangspositie op een samenvloeiing van gebieden waar de Mongo-volkeren wonen ¬ ‘Watermensen', Ngbaka, Ngbandi, enz. Het lijkt een samenvoeging van zowel volkeren en territoria die de sporen dragen van hun versnippering.

De inrichting van Mongala houdt impliciet een identiteitsprobleem in, aangezien het regionale karakter van het district versmolten is in een dubbele tegenstrijdige relatie: langs de ene kant een situatie die zichtbaar is voor de buitenwereld en de ‘autochtonen' confronteert met de naburige etnieën, in het bijzonder de Ngombe tegenover de Mongo, langs de andere kant het onderhuidse conflict, waarbij twee dominante bevolkingsgroepen worden opgevoerd, de Ngombe en de Budja. De spanningen tussen Ngombe en Mongo mogen dan wel opgedoken zijn bij de onafhankelijkheid, rond het politiek leiderschap in de provincie Equateur, hun oorsprong is toch te vinden in de rivaliteit tussen de scheutisten en de missionarissen van het Heilig Hart. De verschillende volkeren van Mongala maken, ruim gezien, deel uit van de Bangala-groep, een supra-etnische identiteit, gebaseerd op de handelstaal van de volkeren die langs de Congorivier gevestigd zijn. Deze taal, die in zijn gesystematiseerde vorm verspreid werd door het onderwijs, werd ook doorgegeven via Force publique.

Van buitenaf gezien vormt de taal ook de identiteit van Mongala, een identiteit die zich op haar beurt zal installeren in het geheel van de provincie Equateur. De Mongo-identiteit werkt als tegengewicht van dit succes, door zich te baseren op de promotie van de Lomongo-taal, die zou moeten fungeren als tegenhanger van het Lingala.

Intern laten de eigenheden zich gelden en raken verankerd tot in de organisatie van het grondgebied. Ngombe en Budja worden rivalen en hun antagonisme komt symbolisch tot uiting in de tegenstelling tussen hun respectieve administratieve hoofdplaatsen. Het bureaucratische Lisala, zetel en brandpunt van onderwijs met culturele uitstraling, kijkt minzaam neer op het handeldrijvende Bumba en zijn nabijgelegen plantages, het centrum van de bevolking en van de economische activiteiten in het noorden van het land.

Het woud is alomtegenwoordig in dit gebied, waar op gezette tijden ook landbouwgewassen worden geteeld. Zijn natuurlijke rijkdommen hebben altijd aanleiding gegeven tot afgunst: Ze maken dat in de regio exploitatiemethodes worden gehanteerd die nog altijd tot controverse leiden. De menselijke activiteiten vertonen er al de kenmerken van een extraverte economie, waarvan de kosten (zowel op menselijk als milieuvlak) overigens werden gedragen door Mongala sinds het einde van de 19e eeuw. De stigmata van het ‘rode rubber' zijn er lang levendig gebleven en de recente campagnes tegen plunderingen in het woud lijken hiervan een weerspiegeling te zijn en impliceren daarnaast nog de delicate thematiek van de (bos)milieubescherming. Van verleden tot heden vormt de rivier en zijn aftakkingen een van de belangrijkste elementen – zo niet hét belangrijkste – van continuïteit in de lokale economische veranderingen.

Het waterwegennet van Mongala vormt een knooppunt met verschillende grondgebieden en verbindt Mongala met het district van de provincie Equateur en Kinshasa, met Sud- en Nord-Ubangi, Ituri en de twee Ueles, tot Aketi en, ten slotte Kisangani. Bumba en Lisala trekken de landbouwoverschotten en bosproductie van hun hinterland naar zich toe om deze dan via de rivier door te sturen naar naburige streken of over land naar de Centraal-Afrikaanse Republiek (via Akula-Zongo). Gedragen vooral door dit natuurlijk netwerk, vormt Mongale een belangrijke productiedraaischijf in heropbloei. Dit, samen met een bevoorrechte geostrategische ligging, maken het gebied uitermate geschikt voor talrijke ontwikkelingsprogramma's van zowel overheid als privé-initiatiefnemers.

***

Despite its 58,141 km2, Mongala, with only three territories, is the smallest administrative group of the 26 provinces of the DRC as laid out in the Constitution of 18 February 2006.

Its organization reflects political and administrative considerations. Mongala thus stretches from west to east, the result of a desire to bring together a core of the Ngombe around Lisala and to include the Budja, established in Bumba territory, and traditionally related to the populations in Province-Orientale (Mbole/Mobango, etc.). In 1955, during the last major administrative reform of the Belgian Congo, Bongandanga was appended. This turbulent history expresses a disparate whole, which appears to be the effect of a geographic position that is a transition point in the confluence between the spaces for the Mongo, ‘people of the water', Ngbaka, Ngbandi, etc. and which makes it appear to be a gathering of peoples and territories marked by their dispersion.

The creation of Mongala implicitly raises the problem of identity, as the regional particularity of the district arose from two competitive relationships: the exterior one pitting the ‘locals' with the neighbouring ethnic groups, particularly the Ngombe with the Mongo; and the internal one, involving two dominant populations, the Ngombe and the Budja. While the tensions between the Ngombe and the Mongo emerged around political leadership in Équateur province at the time of independence, they find their roots in the rivalry between the Scheut fathers and the Sacred Heart missionaries. The various peoples of Mongala belong, in a broad sense, to the Bangala, a supraethnic identity based on the language used in trade by peoples living along the Congo river. Codified and spread by the school system, the language also widened in reach through the Force Publique.

From the outside, it shaped the identity of Mongala, an identity that would in turn overtake the Equateur province. Mongo identity acted as a counterweight to this success, by promoting the Lomongo language which was supposed offset the influence of Lingala.

Internally, differences hardened and affected even the organization of space. A rivalry was born between the Ngombe and the Budja and their antagonism was expressed symbolically in the opposition between their respective administrative centres. Lisala-the-bureaucrat, seat and centre of instruction and cultural influence, used familiar terms to address Bumba-the-trader and its surrounding farmland, the focal point of the populations and economic activities in the country's north.

An area dominated by forest and used in places for crop farming, its natural riches have always been coveted. Such riches made the region a site of still-controversial operations. Human activity there bears all the marks of a booming economy, for which Mongala paid the (human and environmental cost) already in the late 19th century. The scars of ‘red rubber' long remained fresh there, and recent campaigns against the desecration of forest seem to echo them, and also poke a finger into the sensitive topic of (forest) environmental protection. From way back in the past up to the present, the river and its branches are one of the – if not the major – elements of continuity in local economic changes.

Serving as the junction of several territories, Mongala's hydrographic network connects the province with the Equateur district and Kinshala, Sud- and Nord-Ubangi, Ituri and the two Ueles, from Aketi and finally, to Kisangani. Bumba and Lisala siphon off the agricultural surplus and forest products of their inland regions to send them via the river to neighbouring regions, or by road to the Central African Republic (via Akula-Zongo). Carried aloft by these natural pathways, Mongala is an important area of production, with its health currently in remission. This, combined with an advantageous geostrategic location, has made it the target of several governmental and private development programmes.

Gratis beschikbaar via deze link

Gratis beschikbaar via deze link