War trophies, ethnographic objects, and political documents obtained by the military officer Émile Storms

06.07.2021

This article studies the context of the acquisition of six objects and documents obtained by Lieutenant Émile Storms (1846-1918) that are now on display in the AfricaMuseum permanent exhibition:

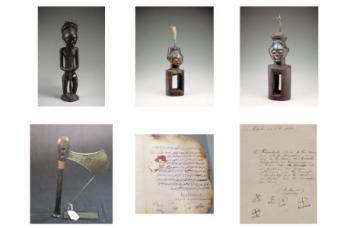

- Statue ‘of Lusinga’ (EO.0.0.31660);

- Two statues of the ancestors of the Tabwa chief Kansabala Kisuyu (Kansawara, Cansawara, Kassabala) (EO.0.0.31663 & EO.0.0.31664);

- First Act of surrender of Chief Kansabala (HA.01.0017.50.1);

- Second Act of surrender of Chief Kansabala (HA.01.0017.50.6);

- Parade axe (EO.0.0.31715).

These six objects and documents are part of a far larger set. The collection donated to the museum in 1930 by the officer’s widow, Henriette Dessaint, comprises:

- nearly 340 ethnographic objects, including some twenty musical instruments;

- several documents, notably 6 treaties of surrender by African chiefs;

- a number of items from Storms’s kit.

Collected under the auspices of the Association internationale africaine

The Association internationale africaine (AIA) was an organization created by Leopold II in 1876. Portrayed as philantrophic, its declared mission was ‘to bring civilization’ to Africa and fight slavery there. This humanitarian cover was used by Leopold II to conquer then exploit territories in Africa. The AIA’s actions paved the way for the creation of the Congo Free State in 1885.

In 1882, Storms left Belgium for an ‘exploratory’ mission on behalf of the AIA, as the commander of the ‘4e Expédition africaine de la côte orientale’ (4th African expedition of the eastern coast’) which reached the Lake Tanganyika area. Exploration of the lake’s west bank led to the creation of the Mpala/Lubanda station on 10 May 1883, where Storms stayed for more than two years, right until he left Congo for good in July 1885.

The pieces donated to the museum after the death of Storms were collected during this mission.

Storms’s collections, including ethnographic objects, were twice damaged extensively, if not lost outright:

- on 14 February 1885, Storms noted in his journal: ‘my ethnographic collections have been largely destroyed by white ants [Editor’s note: termites], and the ones entrusted to the station by the German caravan are in an even more pitiful state’;

- on 19 May 1885, Storms recounted an attack that led to the near-total destruction of the Mpala station by fire: ‘It is a sad sight, all my collections are gone, 150 photographs, collections in natural history, ethnography, physics, geology, mineralogy, etc., etc. Journals, letters, in a word, everything.’

This episode is undoubtedly the reason for the partially-burned state of some of Storms’s documents (including Kansabala’s first Act of surrender, discussed below). The fire may also account for the lack of photographs of the chiefs Lusinga and Kansabala.

Statue ‘of Lusinga’

- EO.0.0.31660

- Exhibited in the Colonial History gallery

- Marungu region

- Sculpted in the 19th/ 2nd half of the 19th century

- Probably crafted by order of the Tabwa chief Lusinga lwa Ng’ombe (ca. 1840-Dec. 1884)

- Property of Tabwa chief Lusinga

- Probably seized by men under the command of Émile Storms during a punitive expedition on 4 December 1884, during which Lusinga was decapitated

- July 1885: the statue leaves Mpala/Lubanda with Storms who returns to Belgium on 21 October 1885

- Collection of Émile Storms, 1885-1918

- First described in print in 1886 (Jacquemont & Storms 1886-1887)

- Storms dies in Brussels on 12/01/1918

- Collection of Henriette Dessaint, widow of Émile Storms, Ixelles, 1918-1930

- Donated to the museum by Henriette Dessaint in 1930

- Significant expography

This statue represents the male ancestors of Lusinga lwa Ng’ombe (ca. 1840-1884), a Tabwa chief of the Marungu region in the east of present-day DR Congo. The main opponent and adversary of the Belgian officer Émile Storms who wanted to gain control of the territories west of Tanganyika, Lusinga was decapitated during a punitive military operation organized by Storms on 4 December 1884.

The conquest of Lusinga, culminating in his violent death, led to the surrender of numerous chiefs in the area. For Storms, it also triggered a war that allowed the officer to establish his dominance. The event left a vivid mark. In the 1970s, Mpala elders still knew the spectacular and macabre tale of this historical episode, from the attack on Lusinga to the victorious procession of Storms’ men upon reaching the station with their spoils (Roberts 2013 : 58).

In addition to the head of his foe as a trophy, supplies and goods – undoubtedly including this statue – were plundered.

In taking the statue, Storms symbolically reinforced his victory by seizing the depiction of the dynastic line of the dead chief. Its inclusion in the officer’s private collection (until his death) in Belgium attests to its value as a ‘war trophy’. For years it was displayed in an installation of paraphernalia in the drawing room of his Brussels home.

Congolese artist Aimé Mpane represented the skull of Tabwa chief Lusinga in the museum’s grand rotunda. Brought to Belgium along with the skulls of two of the region’s other chiefs (Maribu and Mpampa), this relic stayed in Storms’s personal collections. It was then donated to the Tervuren museum in 1935 (where it was included in the Physical Anthropology section) before being transferred in the 1960s to the Royal Museum of Natural History, now the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. The skulls of Lusinga and Maribu are still conserved at the RBINS. Mpampa’s skull remains in the RMCA collections (Volper 2021).

Mpane’s work is part of the current debate on the presence of such ‘human remains’, obtained from colonial conquest and occupation, in Belgium’s national collections, and more broadly on the violence – both physical and symbolic – behind these collections. In 2020, in collaboration with six other museums and universities, the RMCA launched the HOME project to conduct a detailed assessment of the historical, scientific, and ethical contexts surrounding human remains in Belgian collections. Its goal is to inform policymakers and relevant parties of the possibilities regarding the ultimate purposes of these remains.

Two statues of ancestors of Tabwa chief Kansabala

- EO.0.0.31663 & EO.0.0.31664

- Exhibited in the Rituals and Ceremonies gallery

- Marungu region

- Sculpted in the 19th century

- Probably crafted by order of Tabwa chief Kansabala Kisuyu (?-late October 1885), a relative (maternal uncle) of Lusinga

- Property of Chief Kansabala

- March 1885: Storms’s men conduct raids in the fortress of Kansabala, Marungu region

- July 1885: Storms leaves Mpala/Lubanda and returns to Belgium with the two statues

- Collection of Émile Storms, 1885-1918

- Mid-September 1885: Kansabala surrenders in Lubanda and surrenders a second time at the Mpala station

- 21 October 1885: Storms arrives in Belgium

- Late October 1885: death of Kansabala

- February 1886: ritual burial of Kansabala in Lubanda

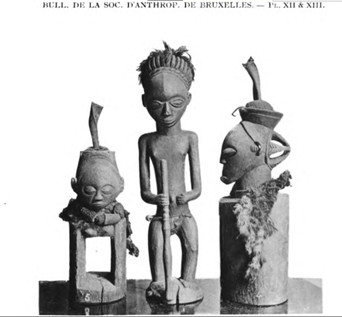

- First described in print in 1886 (Jacquemont & Storms 1886-1887)

- Storms dies in Brussels on 12/01/1918

- Collection of Henriette Dessaint, widow of Émile Storms, Ixelles, 1918-1930

- Donated to the museum by Henriette Dessaint in 1930

- Significant expography

Kansabala (or Kansawara) was one of the chiefs who surrendered to Storms after Lusinga’s defeat, pledging allegiance to the station founded in Mpala by the Belgian officer. In 9 December 1884, Storms writes in his journal:

‘Je suis en négociation avec Kansawara le plus grand chef du Marungu pour lui faire reconnaître ma suzeraineté.’

‘I am negotiating with Kansawara, the most important chief in Marungu, to recognize my suzerainty.’

And on 15 December 1884, he writes:

‘Kansawara envoie une ambassade pour me donner réponse à l’ordre que je lui ai fait parvenir de se ranger sous ma souveraineté et comme marque de soumission qu’il a à me payer un hongo en houes. L’ambassade est conduite chez moi par Mpala qui sert d’interprète aux gens de Kansawara. Mpala transmet les paroles dites au nom de Kansawara à mon nyampara qui à son tour me communique ce qui lui a été dit. […] Kansawara me fait savoir qu’il n’a pas pu répondre plus vite à ma demande parce qu’il avait dû consulter tous ses chefs à ce sujet, et que sa contrée étant grande il avait fallu plusieurs jours pour les réunir. […].’

‘Kansawara sent emissaries in response to the order I sent him to accept my sovereignty and to pay me a hongo in hoes to mark his surrender. The envoys were brought to me by Mpala who served as an interpreter for Kansawara’s people. Mpala conveyed the speech in Kansawara’s name to my nyampara who in turn told me what he heard. […] Kansawara informed me that he had been unable to reply to my order earlier as he had to consult all his chiefs about it, and that it had taken several days to bring them together given the size of his lands. […].’

A treaty of surrender was signed that day between Storms and Kansabala’s representatives. One of the original versions of the document, dated 15 December 1884 and written in Arabo-Swahili, is conserved at the RMCA. It is exhibited in a showcase in the Languages and Music gallery (see below).

A few weeks after the initial surrender, Storms nevertheless clashed with Kansabala on the pretext that the chief had participated in naming a successor to Lusinga without consulting him.

Kansabala’s village was thus destroyed on 22 March 1885, while the chief found refuge with one of his allies, Louike.

In a journal entry dated 27 March 1885, Storms describes the large haul of sculptures seized by his men:

‘Du village de Kansawara me viennent beaucoup de fétiches et des idoles. Ces dernières ne sont pas des idoles comme nous nous les figurons, on ne leur voue pas un culte. Dans les cases des chefs elles représentent généralement leurs aïeux. Elles sont placées dans des petites cases spéciales et chaque fois que le chef boit du pombé elles en ont leur part. On place généralement à côté d’elles les dawa dont se servaient ceux qu’elles représentent.’

‘Many fetishes and idols have been brought to me from Kansawara’s village. The latter are not idols as we understand the term; they are not worshipped. In the homes of chiefs, they generally represent ancestors. These idols are placed in small special cases and each time the chief drinks pombe, they receive a share. The dawa used by the persons they depict are usually placed beside them.’

Like Lusinga’s statue, Kansabala’s sculptures were described in print in 1886 in an ethnographic study co-authored by Storms. Back then, along with horns, the two statues also sported other components, in particular necklaces and skins that went missing over time. In 1929, before they entered the museum, furred elements already seem to have disappeared (see photos HP.1930.653.4 & HP.1930.653.5; note however that ornaments had been added). Today, only the cords of the impressive ‘necklaces’ that once decorated the figures remain.

Just like the simplified structure of the bodies, the missing components characterize another function of these sculptures. Not only did they represent ancestors of the royal line of Kansabala, but they also carried powerful protective magic charms. Storms’s knowledge undoubtedly allowed him to see the strategic benefits he could glean from obtaining such objects, stolen from his enemy.

First Act of surrender of Chief Kansabala

- Exhibited in the Languages and Music gallery

Original French translation:

‘Le 28 du 5e mois de la [sic]

Le 15 décembre 1884,

Copie du PV par lequel le roi Kansawara cède ses pouvoirs à l’Association – Traduction,

Je soussigné, Paul Reichard, commandant de l’expédition allemande de l’Association internationale, déclare avoir assisté à l’entrevue qui a eu lieu entre : Monsieur Storms agissant au nom de l’AIA d’une part et une ambassade envoyée par le roi Kansawara agissant au nom de ce souverain d’autre part.

Le roi Kansawara fait savoir : qu’après la défaite et la mort de Lusinga, il a réuni tous ses chefs pour savoir la conduite qu’ils avaient à tenir vis-à-vis du vainqueur de Lusinga. Qu’après délibération il a été décidé que : le roi Kansawara et tous les siens reconnaissaient l’autorité de l’Européen en résidence à Mpala et qu’il remettait entre ses mains les pleins pouvoirs sur toute l’étendue de leurs contrées.

Le roi Kansawara a confirmé cette déclaration en payant hongo.

Cette façon de procéder est conforme aux us et coutumes de la contrée en pareille circonstance.’

‘On the 28th of the fifth month of the [sic]

On 15 December 1884,

Copy of the report in which the king Kansawara relinquishes his powers to the Association – Translation,

I the undersigned, Paul Reichard, commander of the German expedition of the International Association, declare

that I was present at the talks between: Mr. Storms acting on behalf of the AIA on one hand, and a

delegation sent by King Kanswara acting in his name on the other hand.

King Kansawara has conveyed: that after the defeat and death of Lusinga, he has gathered all his chiefs to decide

upon their conduct with regard to Lusinga’s conqueror. After deliberations, it was decided that: King

Kansawara and all his subjects recognize the authority of the European in residence at Mpala, and surrender

to him full powers over their lands.

King Kansawara has confirmed this declaration by paying a hongo.

This way of proceeding is in line with the customs of the land in such circumstances.’

Only the French translation included a nota bene listing the ‘major centres of the states of Kansawara’ which over 50 place names.

The present-day translation by X. Luffin (published in 2020) varies slightly and is no doubt more accurate/literal in its contents:

‘Le vingt[-huit] du 5e mois,

Monsieur Storms, qui représente l’Association internationale africaine, et les émissaires du roi Kansawara, qui ont été envoyés par celui-ci parce qu’il ne pouvait pas venir lui-même, ont tenu conseil sur son territoire. Kansawara a rassemblé ses hommes et a tenu conseil avec leurs chefs. Il a déclaré qu’après la défaite et la mort de Lusinga, il fallait tenir un conseil pour décider de l’avenir du pays. Lorsqu’ils ont fini leur conseil, il a dit que le roi Kansawara, ses hommes et ses chefs acceptaient l’autorité des Blancs qui se trouvent à Mpala et que leur force appartenait désormais aux Blancs. Enfin le chef Kansawara a envoyé son tribut aux Blancs pour qu’ils sachent qu’il considère réellement être sous leur autorité, conformément aux coutumes du pays. Moi, Paul Reichard, responsable de l’expédition allemande, j’ai assisté à toute la discussion en tant que témoin.’

‘On the twenty-[eighth] of the 5th month,

Mr. Storms, representing the Association international africaine, and the emissaries of King Kansawara, who were sent by the latter as he was unable to attend in person, conferred on his territory. Kansawara had gathered his men and deliberated with their chiefs. He declared that after the defeat and death of Lusinga, a council needed to be held to decide upon the country’s future. At the end of their council, he said that King Kansawara, his men and his chiefs accepted the authority of the Whites in Mpala and that their strength belonged henceforth to the Whites. Finally, Chief Kansawara sent his tribute to the Whites to prove that he was truly under their authority, in accordance with the customs of the land. I, Paul Reichard, head of the German expedition, attended the entire discussion as a witness.’

Only the signatures of Reichard and Ramazani are written out in full, while other names were simply scribbled.

[In German:] Paul Reichard, Chef der deutschen Expedition;

Hamisi, Mwenye Kombo, Said, Sadala, Ramazani, [Mpala]

Chief Kansabala twice signed an Act of surrender in the station established by Storms in Mpala. The first of the two documents was signed by emissaries in the name of their king. It was written in Arabo-Swahili before several witnesses, including the chief Mpala (Storm’s ‘blood brother’) who served as the interpreter for the occasion.

There are two Arabo-Swahili version of this treaty. The first is conserved along with its original French translation, provided by Storms, in the former African Archives of Belgium. The second version is conserved at the RMCA, and the gallery exhibits a reproduction thereof. A third version was probably drafted for Kansabala at the time.

While there are slight variations between the two known Arabo-Swahili versions (Xavier Luffin suggests the presence of several scribes), the French translation provided down by Storms diverges significantly from the original texts.

Storms himself acknowledged that the text was adapted for a European readership. It was in effect meant for the secretary-general of the AIA in Brussels and, through him, the representatives of the Western powers (who could eventually dispute Leopold II’s sovereignty over these territories).

In doing so, Storms fulfilled the directives of Maximilien Strauch, one of Leopold II’s advisers and AIA secretary-general, who wanted the surrender of sovereign rights to be worded concisely and efficiently in treaties:

‘Il faut que ces traités soient aussi courts que possible et qu’en un article ou deux, ils nous accordent tout.’

‘These treaties must be as brief as possible; they should grant us everything in an article or two.’

Leopold II to Strauch, 5 Oct. 1882 and 15 oct. 1882, Strauch papers, nos. 125 and 129, Ministry of Foreign Affairs

(Denuit-Somerheusen 1988 : 87).

Wording thus varies somewhat between a contemporary literal translation (Luffin 2007):

‘le roi Kansawara, ses hommes et ses chefs accept[ai]ent l’autorité des Blancs qui se trouvent à Mpala et [que] leur force [appartenait] appartient désormais aux Blancs.’

‘King Kansawara, his men and his chiefs accept[ed] the authority of the Whites in Mpala and [that] their forces belong[ed] henceforth to the Whites.

and the one provided by Storms:

‘le roi Kansawara et tous les siens reconnaiss(ai)ent l’autorité de l’Européen en résidence à Mpala et [qu’]il remet[tait] entre ses mains les pleins pouvoirs sur toute l’étendue de leurs contrées.’

‘King Kansawara and all his subjects recognize[d] the authority of the European in residence at Mpala, and surrender[ed] to him full powers over their lands.’

Moreover, only the French version written by Storms enumerates the names of more than 50 villages affected by the treaty.

Although slight, these differences in form reveal the divergent interpretations of what the documents signify. From the Congolese viewpoint, a chief’s surrender, formalized here by the payment of a hongo, does not necessarily imply the outright relinquishment of all territorial and political sovereignty. Yet this is what the text means to the Europeans in Mpala: placing all of Kansabala’s lands under the authority of the AIA represented by Storms, for all forms of political intervention, to ultimately legitimize the (then-imminent) recognition of a ‘Leopoldian’ sovereignty over these territories.

Second Act of surrender of Chief Kansabala

- Exhibited in the Colonial History gallery

Transcription:

‘Kassabala vient de lui-même faire acte de soumission au chef de la station de Mpala, apportant en témoignage un tribut selon les us et coutumes du pays. Il reçoit avec la promesse d’être protégé par nous un terrain qui lui est assigné par nous.

[signatures :] I. Moinet, supérieur / Kiwe / Kassabala / Mkala ou Ukala’

‘Kasabala himself has just surrendered to the chief of Mpala station, bringing tribute as is customary. Along with our pledge to protect him, he also receives a piece of land that we have assigned him.

[signatures:] I. Moinet, superior officer / Kiwe / Kassabala / Mkala or Ukala’

Kansabala (as well as several Congolese witnesses) signed this text drafted by Father Isaac Moinet (the officer-in-charge at the Mpala station in the absence of Storms) with a cross.

The battle between Kansabala and Storms lasted until the latter’s return to Belgium.

After preparing a new expedition against Kansabala (300 men, all reinforcements from allied chiefs), on 11 April 1885, as the armed column was to depart, Storms wrote down the explanation for such tenacity in his journal:

‘Voilà toute une série de guerres qui s’enchevêtrent et dont la cause première est bien simple ; Lusinga ayant surpris et détruit un village qui se trouvait sous mon protectorat, j’ai fait la guerre à Lusinga pour faire respecter les miens. Lusinga tué, la joie était grande dans toute la contrée, mais bientôt ils ont oublié la terreur que Lusinga inspira naguère et on me reproche, du moins dans quelques contrées, d’avoir tué un de leurs chefs. Mais si d’une part cette guerre a des inconvénients à cause de la façon même de faire la guerre dans cette contrée, elle nous assure une autorité prépondérante dans la contrée.’

‘Now we have a string of entangled wars whose main cause is quite simple. After Lusinga took a village under my protection by surprise and destroyed it, I waged war against Lusinga to make him respect what was mine. The death of Lusinga was greeted with great joy all over the land, but they soon forgot the terror he once inspired, and in some parts at least they rebuke me for having killed one of their leaders. But while this war has drawbacks because of the way they fight here, it ensures our predominant authority in this land.’

Despite several alliances formed officially by, among others, the signing of treaties (in addition to the 6 that reached the museum, Storms mentions several others in his personal writings), using arms to obtain surrender was an indispensable principle for Storms. In his view, any power that was not based on military force was an illusion, and he thus justified responding to any (apparent) offense with an implacable violence so that he would not lose his authority, or even his life. In a journal entry dated 1 December 1884, Storms decried the overly respectful British campaigns that were not aggressive enough for him. And in reference to the occupation of territory by the Arabo-Swahili, he declared: ‘D’ailleurs dans toute l’Afrique on ne reconnaît d’autre conquête que celle faite par les armes’ (‘Besides, all over Africa, only conquest by force is recognized as true conquest’).

Several months after Storms left for Belgium, Kansabala finally pledged allegiance for the second time at the Mpala station on 29 September 1885, in a document that also entered the museum via the collection of Storms, who received it from Father Isaac Moinet, the officer’s unofficial successor in Mpala.

Their correspondence reveals that the system established by Storms continued to be used:

‘Le 24 [septembre 1885], nous continuâmes nos manœuvres au nom de l’association, je donnai notre pays, rive gauche du Lufuka à Mwana Mungu [?], Mama Kaomba et Kassabala qui, m’accompagnant, reçu ordre de ma part d’aller leur déterminer un emplacement pour y construire leur ville et s’y fortifier avec ordre aux chefs dans 5 jours de venir à la station afin […] de signer l’acte dont je vous enverrai copie. J’ai voulu prendre tout cet appareil afin d’imiter votre manière de faire et que les sauvages/chefs soumis n’aient rien à dire.’

‘On 24 [September 1885], we continued our manœuvres in the association’s name, I gave our land on the left bank of Lufuka to Mwana Mungu [?], Mama Kaomba and Kassabala who, in my company, received my order to find a spot for their town and build their strength, with an order to the chiefs to come to the station in 5 days in order to […] sign the act, a copy of which I shall send you. I wanted to take all these measures to imitate your methods and so that the savages/chiefs under submission have nothing to say.’

This remote monitoring shows the personal nature of the domination exercised by Storms over what some of his contemporaries clearly perceived as ‘his kingdom’ of Mpala/Lubanda and its surroundings.

The autonomous and somewhat erratic operations of the Mpala station continued for some time, a situation that Storms’s detractors did not fail to note at the time in referring to him sarcastically as ‘Émile the first, Emperor of Tanganika’ (Le Mouvement géographique 1885: 69).

In his writings, Moinet is very pleased with the impact of Kansabala’s full surrender. Upon the chief’s death (of old age) less than a month later in late October 1885 during a smallpox epidemic, Moinet followed the burial with great attention and closely supervised the designation of his successor.

Parade axe

- Exhibited in the Long History gallery

The collection of nearly 340 objects and documents brought to Belgium by the military officer Émile Storms included some one hundred weapons, including seven axes.

A comparative approach led to the attribution of this parade axe to the Tetela peoples of the region of Sankuru, in the centre of present-day DR Congo. Yet Émile Storms never went to that area. Some of the objects he collected were nonetheless identified by him as coming from Maniema, a zone also occupied by the Tetela and located between Sankuru and Marungu, where he had established a post on Lake Tanganyika’s west bank. At the time, Tetela groups had had trade relations for several years with the Arabo-Swahilis, particularly the Zanzibar merchant Tippo-Tip, which led to extensive circulation of persons and objects in all these regions.

Owing to the lack of data in the archives, it is impossible to determine a precise geographic ‘provenance’ for this piece (like many other pieces in the museum). But it is also possible that such information has unfortunately been lost.

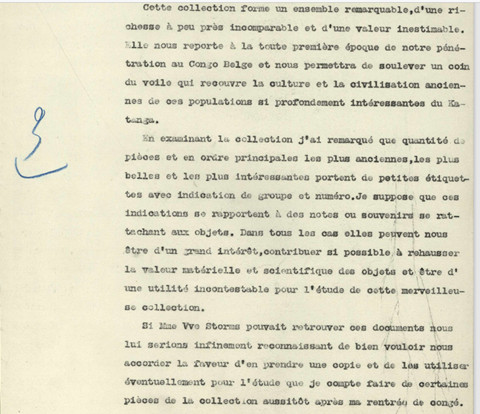

In a letter to the museum director, the conservator J. Maes (acquisition dossier of 09/05/1930) mentions:

‘En examinant la collection, j’ai remarqué que quantité de pièces […] portent de petites étiquettes avec indication de groupe et numéro. Je suppose que ces indications se rapportent à des notes ou souvenirs se rattachant aux objets. […] Si Mme Vve Storms pouvait retrouver ces documents nous lui [en] serions infiniment reconnaissant […]’

‘In examining the collection, I noted that several pieces […] bore small labels noting group and number. I suppose that these indications refer to notes or memories relating to the objects. […] If the widow Madame Storms could find these documents we would be infinitely grateful […]’

The existence of additional sources of information to narrow down the provenance of the collections is often mentioned by Maes in his opinions regarding the museum’s potential acquisitions. Such arguments in favour of purchase showed awareness of the value added by these details. We must nonetheless note that after acquisition, such information can rarely be found in the documentation available today.

Text compiled from a draft by Agnès Lacaille based on specific research and a synthesis of the data below.

SOURCES

Interviews, indirect/unpublished sources: Mathilde Leduc-Grimaldi, Xavier Luffin, Hein Vanhee, Anne Welshen.

Archives:

- State Archives of Belgium: SPA, General dossiers, Register no. 767, no. 81.

- Archives of the Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs: AAAI 1377 (Émile Storms bundle).

- Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and Military History: dossier STORMS Émile P. J., no. 8547.

- Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Ethnography Section, Acquisition files, DA.2.529.

- Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Fonds Émile Storms, « Journal du lieutenant Storms, … », Journal de la quatrième expédition de l'AIA, HA.01.0017.27.

- Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Fonds Émile Storms, Isaac Moinet, HA.01.0017.20.

- Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Fonds Emile Storms.

Publications (articles and books):

- ARSOM. 1988. Le Centenaire de l’Etat indépendant du Congo. Collection of studies. Brussels: RAOS, 533 p. Available online

- Coosemans, M. 1948. ‘Storms Émile Pierre Joseph, belge’. In Biographie coloniale Belge. Brussels: Institut royal colonial belge, vol I, col. 899-903.

- Denuit-Somerhausen, C. 1988. ‘Les traités de Stanley et de ses collaborateurs avec les chefs africains, 1880-1885’. Recueil d'études. Le centenaire de l'État Indépendant du Congo. Brussels: Royal Academy for Overseas Sciences, pp. 77-146.

- Jacquemont, V. & Storms, E. 1886-1887. ‘Notes ethnographiques sur la partie orientales de l’Afrique équatoriale’. Bulletin de la société d’Anthropologie de Bruxelles, t. V.

- Luffin, X. 2007. ‘Cinq actes de soumission en swahili en caractères arabes du Marungu (1884-1885)’. Annales Aequatoria 28: 169-199.

- Le Mouvement géographique. 1885, 17: 69.

- Roberts, Allen F. 2013. A Dance of Assassins. Performing Early Colonial Hegemony in The Congo. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 311 p.

- Roberts, Allen F. 2018. Lusinga in Los Angeles. Online: https://www.lusingatabwa.com/2018/03/lusinga-in-los-angeles.html

- Roberts, Allen F. 2000. ‘Tawba statues’. In: Verswijver et al., Treasures from the Africa-Museum, Tervuren. Tervuren: RMCA, pp. 368-369.

- Roberts, Allen F. & & Maurer, E.M. 1986. Tabwa Art. The Rising of the New Moon. Tervuren: RMCA, 288 p.

- Volper, J. 2012. ‘Of sculptures and skulls. The Émile Storms Collection’. Tribal Arts 66: 86-95.

- Volper, J. 2021. ‘La mort et son numéro d’inventaire. Quelques réflexions autour des crânes humains en collections muséales’. In Th. Beaufils & Ch. Ming Peng (eds), Histoire d'objets extra-européens: collecte, appropriation, médiation. Villeneuve d’Ascq: Publications de l’Institut de recherches historiques du Septentrion, ‘Histoire et littérature du Septentrion (IRHiS)’ series, no. 66. Available online

- Wastiau, B. 2006. ‘The scourge of chief Kansabala: the ritual life of two Congolese masterpieces at the Royal Museum for Central Africa (1884-2001)’. In: M. Bouquet & N. Porto (eds), Science, Magic and Religion: The Ritual Processes of Museum Magic, New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books, pp. 95-116. Available online

The information in this article is based primarily on resources available at the museum (archives, publications, etc.). The descriptions of these objects and documents can thus always be expanded. Do you have comments, information, or testimonials to share about these or similar objects? Don’t hesitate to contact us: provenance@africamuseum.be.

In the framework of the Taking Care project.